Annie Reynoso wanted a tummy tuck. But her doctor said no. Uterine fibroids meant she wasn’t a good candidate for abdominal surgery. He had an idea though, the doctor. If what Annie was looking for was a physical boost, there were other options out there. Like breast implants.

Annie, then 32, looked down at her boobs. She felt a little uncomfortable, like she was being upsold. But it was true, they were droopy. They could use some oomph. Plus, this was supposed to be a birthday gift to herself, something just for her. She’d been saving up for years. So she went for it: $4,500 implants that took her from a C- to a D-cup.

She didn’t regret it. Not at first anyway. Her new breasts were perky. They did have oomph. They filled out shirts and dresses in a way that made Annie feel good about her body. She forgot all about the tummy tuck.

Then it was a few years later, and odd things started happening: Her breasts swelled to a G-cup. She had fatigue that would knock her out for days. Sudden dizzy spells made it scary for her to drive. She’d get short of breath after walking just a few steps. She had night sweats that soaked her mattress. And there were even stranger symptoms: nausea if she ate before noon, and pain in her chest, neck, ears, and jaw that felt like the worst sunburn of her life. She kept tubes of Aspercreme in her purse, coat pockets, and desk drawer. At least a dozen times a day, she had to slather herself in ointment.

Throughout 2018, Annie got mammograms, blood tests, biopsies, MRIs, CT scans, an echocardiogram, and more. The results turned up nothing. Or almost nothing. One doctor diagnosed her with a fast heart rate. After a large lymph node was discovered on her neck, she got a biopsy. Still no conclusive answers. At this point, even though she had good health insurance, she was shelling out hundreds of dollars for co-pays and out-of-network specialists. The tests added up.

Annie paid for them all, until she lost her job as a mental health advocate, which she did full-time while also going to school. She’d been good at it, but she was always sick. And with so many bills and no income, she slid $7,000 behind in rent on her New York City apartment. More than once, she came home to an eviction notice taped to her door. Her car was almost repossessed; she cashed out her 401(k). Between the stress of her money problems and her illness, she failed four of her college classes, leaving her unable to graduate.

That’s when something finally changed: A friend of Annie’s started feeling better after her implants were removed, and a rheumatologist told Annie some of her symptoms aligned with Sjögren’s syndrome, an autoimmune disease potentially triggered by her implants. After that, all she could think about was getting them out.

Once again, she waited in a surgeon’s office. A new one this time. She’d gotten her implants in the Dominican Republic, where her family lives and they could help her through the recovery. Now she sat alone in New Jersey, consulting with a doctor about having her implants removed in a procedure called an explant. She was hopeful. Until she was told it would cost $7,500—and that insurance wasn’t likely to cover a dime.

It had nothing to do with where she’d gotten her implants—insurance companies generally don’t reject coverage for complications just because an initial surgery took place out of the country. It had everything to do with the fact that insurers just don’t cover the explant Annie needed, even though she wasn’t changing her mind for aesthetic reasons. Even though she was dangerously sick and had reason to believe she’d never get better as long as the implants were in her body. Even though she didn’t have close to $7,500.

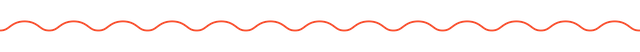

When it comes to popular plastic surgeries, boob jobs are at the top of the list. They’ve been the most performed cosmetic procedure in the country for 13 years straight. In 2019, around 300,000 women got breast implant augmentations, a 41 percent jump from 2000, according to data from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS). (This doesn’t include the additional 107,000 women who got breast implants after a mastectomy and reconstruction, which is considered medically necessary.) Driving the record-setting numbers: Gen Z and millennial women, who make up nearly 70 percent of breast implant surgeries.

The uptick has no doubt been helped along by a ground-level plastic surgery economy—no-surgery nose jobs, lunchtime lipo, in-and-out injectables—that makes getting nipped, tucked, and filled seem as easy as getting a bikini wax or a teeth-whitening treatment.

It seems that way because that’s exactly how it’s sold. “Some plastic surgeons have adopted an attitude of ‘I’ll inform you of potential risks but follow up by saying those risks likely won’t happen to you,’” says S. Lori Brown, PhD, a retired FDA researcher. It’s not surprising why: The average surgeon’s fee for a breast implant procedure is around $4,000. Multiply that by 300,000 and there’s your $1.2 billion reason for the “everything will be fine.”

In many cases, doctors are right—everything will be fine. But in a lot of other cases, it won’t. In 2019, nearly 34,000 women had their implants removed, according to the ASPS. A number that has been going up by the thousands the past few years. And a huge chunk of those procedures—explants often cost between $7,000 and $10,000—won’t be covered by insurance, creating a new health and financial crisis for women.

At the heart of it all is something both frustratingly murky and devastatingly clear: Women self-report any number of different symptoms like Annie’s that are believed to be caused by their implants, but there is no official medical term or definition. They have to just call it “breast implant illness.” Many doctors, citing a lack of scientific proof, don’t believe the condition even exists. They rarely warn their patients about it in advance. Insurers don’t acknowledge it at all.

And yet, there is evidence to suggest that breast implant illness might actually be an autoimmune disorder caused by implants. In 2018, a study in the International Journal of Epidemiology found that women with silicone breast implants had more than a 20 percent increased risk of being diagnosed with an autoimmune or rheumatic disorder.

There is also overwhelming anecdotal evidence online, in Facebook groups like Breast Implant Illness and Healing by Nicole, where hundreds of thousands of women share their stories. And of course, there are the endless comments on posts like Chrissy Teigen’s recent Instagram update about having her implants removed. Women saying they wish they could too—women saying, “Having them is making me sick.”

Enter the question you’re probably wondering about right now, which everyone involved in this entire mess has raised at some point: Who should pay when a voluntary procedure goes wrong? For women like Annie, the answer seems obvious. They’re sick, they need health care—health insurance (which, btw, they pay to have) should help them get well.

Still, most insurers won’t. “It’s a bit of a game,” says Scot Bradley Glasberg, MD, former president of the ASPS. “Insurers use the fact that there is no true medical definition or billing code for breast implant illness as an opportunity to try not to pay for it.” When it comes to explants due to breast implant illness, they consider it just as elective as the original implants were. (The exception is for women who undergo breast reconstruction after a mastectomy, including those done for preventive reasons, but even here, there are insurance-friendly loopholes. Some government- and religious-based plans are exempt from having to cover anything, leaving those women to pay for any later complications out of pocket.)

Never mind that insurers often cover the cost of addressing complications from other elective procedures like IVF and gastric bypass surgery. Or even other breast-implant-related complications that they can “see,” like a rupture. And confusingly, breast reductions are often covered in full if a woman can prove she’s in pain and the surgery would end up improving her quality of life.

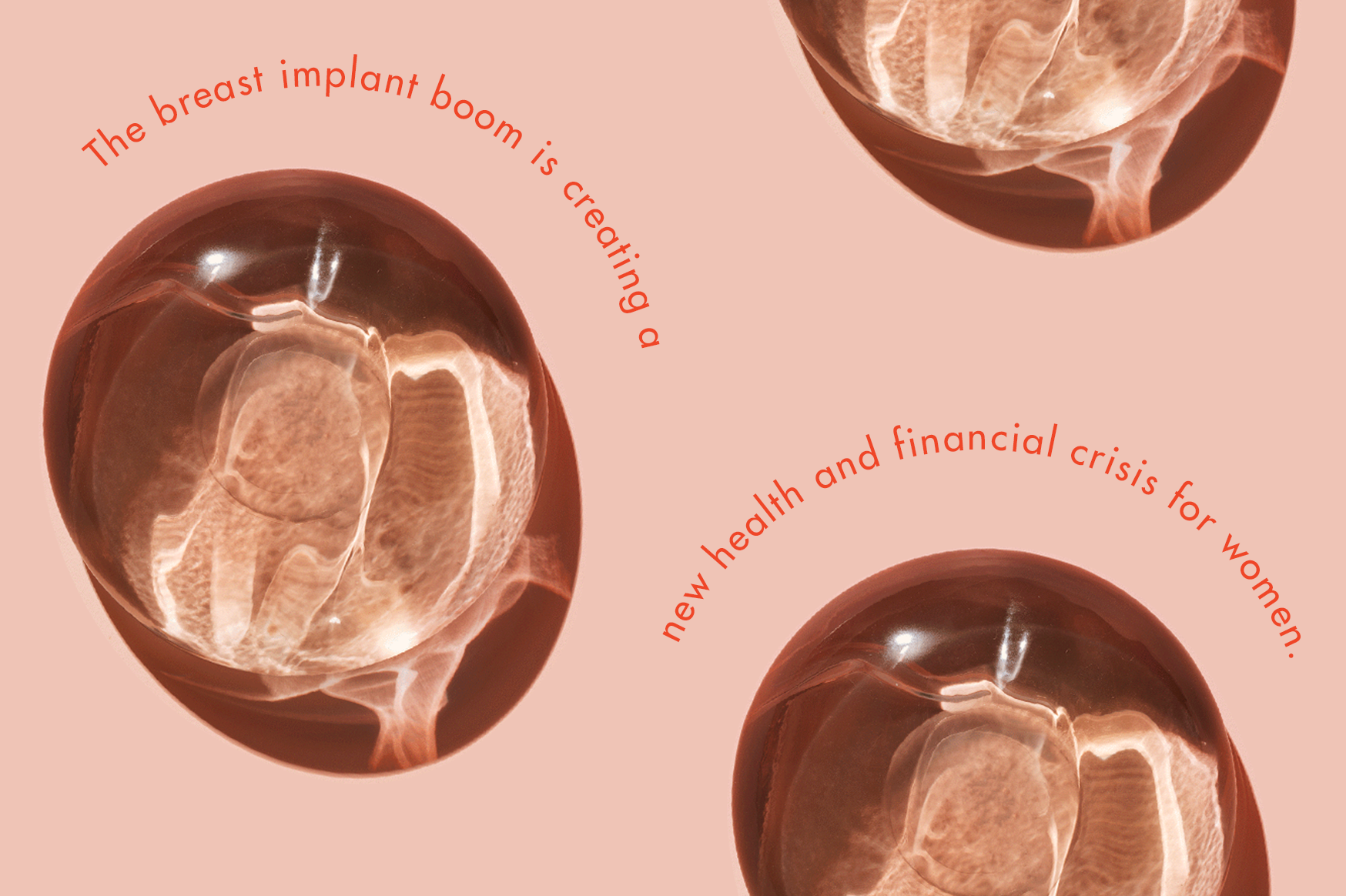

This is mind-boggling to people like Bailey Martindale, 30, who got breast implants to help correct a genetic condition that caused her breasts to grow long and narrow. For her, it was a quality-of-life decision as much as it was a cosmetic one, yet she still paid for them in full. Six years later, she was diagnosed with an autoimmune disease called Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and doctors said removing her implants would likely improve her health. She was also told that the $16,000 for the type of explant she needed was considered elective and therefore not covered. She still hasn’t been able to come up with the money.

For sick women who are financially able to get explant surgery, it can change everything. In a July 2020 study in Annals of Plastic Surgery, researchers found that those experiencing symptoms of breast implant illness saw an improvement in their health within a month of having their implants removed. Like Lauren Dearman, who had explant surgery last November.

She was just 20 when her parents offered to pay $8,000 for her C-cup breast implants. Six years later, she began to have severe abdominal issues and chest pain, bad enough that she went to the ER. She was tired all the time and had such trouble focusing that she couldn’t even write a to-do list. She couldn’t climb the stairs to her third-floor apartment without gripping the railing. Her boyfriend told her she was out of shape. Her boyfriend, she knew, was wrong.

When she came across a Facebook group where women were talking about breast implant illness, the stories read like her own medical file. Within weeks, she made an appointment with a surgeon in Chicago who agreed that her implants could be at the root of her health issues. Lauren cried when she learned how much the surgery would cost. Her parents couldn’t pitch in financially this time, so Lauren withdrew $2,500 from savings and took out a personal loan for $6,500 so she could have the procedure. At $190 a month, she’ll be paying it off for the next three years. But she feels so much better now.

In a health care system that has no problem paying for Viagra (and Viagra overdoses), the fact that women like Lauren have to finance their medical care is infuriating, says Cari M. Schwartz, a lawyer at the firm Kantor & Kantor in California.

Schwartz is working on bringing a class-action lawsuit against insurance companies that deny explant coverage. She’s interviewed hundreds of women across the country desperate to get their implants out. In every case, insurers denied coverage, even when physicians deemed removals medically necessary. Schwartz has seen women rack up credit-card debt, borrow money, lose relationships and jobs, and go bankrupt in an effort to save their health. “Women are essentially told that their health issues are their fault,” she says, “because they chose to get implants.”

In 2019, the FDA said it was putting more effort into educating doctors and patients on the “systemic symptoms” many women with implants experience. Although they also still say they don’t have “definitive evidence demonstrating breast implants cause these symptoms.”

Doctors, too, remain reluctant to get onboard. “To recognize breast implant illness is to kill the goose that laid the golden egg,” says H. Jae Chun, MD, a Newport Beach, California, surgeon who specializes in explant surgery. “And many doctors just aren’t going to mess with the goose.”

In the meantime, one of the only options for desperate patients is the National Center for Health Research’s program to help women navigate the path to explant. They don’t give out money, but if a woman has health insurance, they’ll do what they can to coach her and her plastic surgeon through the insurance maze. Often, that means helping fill out paperwork explaining why the procedure is medically necessary. It’s a process that can take months and still results in a denial the majority of the time, says Diana Zuckerman, PhD, the group’s president. But so far, they’ve helped more than 1,500 women get the explants they need.

Annie doesn’t have the $7,500 for hers yet. She did get a new job and had started saving up, but she lost it during the pandemic. So she’s been scrolling through job listings, many of which tout great health insurance benefits. Not that it matters.

Photos of Annie Reynoso by Adeline Lulo

Photos of Bailey Martindale and Lauren Dearman provided by the subjects

Explant photos by The Voorhes

Catherine Guthrie, author of FLAT: Reclaiming My Body from Breast Cancer, is an award-winning women's health journalist. For the past twenty years, her reporting, essays, and criticism have appeared in dozens of national magazines including Time; O, The Oprah Magazine, Slate; Prevention; and Yoga Journal. She has faced breast cancer twice. She lives near Boston, Massachusetts.