Content warning: This story contains details about violence and sexual assault.

Michael Finton was living in Decatur, Illinois, a shrinking manufacturing town, working as a part-time cook at a cheap take-out joint. He was 29 and unmarried, with red hair and white skin, described as polite by his coworkers, as the mild-mannered guy next door by his neighbors. He liked to hang out and play cards and watch soccer. He also wanted to kill as many people as he could.

But no one knew that yet—except for her.

An elite investigator who tracks angry men online, she’s known to some in her field as the Savant because of her uncanny ability to suss out when, exactly, hate speech will morph into violent action. She came across Finton’s Myspace profile in 2007 and was disturbed by what she saw: videos of Islamic extremists carrying out brutal killings alongside quotes glorifying religious martyrdom. The page gave her a primal, hairs-on-end feeling that she’d learned not to ignore.

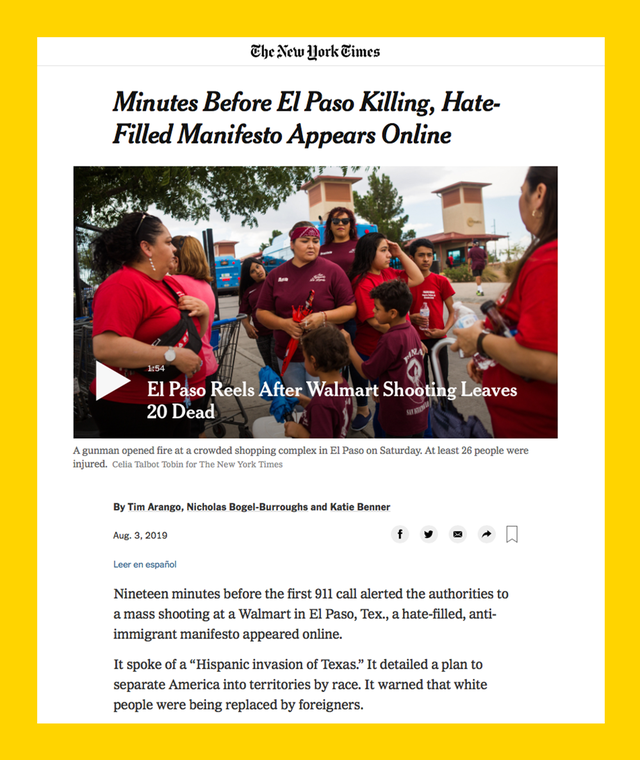

Back then, online rage was still relatively new. This was before Dylann Roof used the internet to self-radicalize, before men flocked to message boards to tap out screeds against women, before the El Paso shooter reportedly dropped his delusional final manifesto on social media. Back when you could post all the crazy shit you wanted online and no one really took you seriously.

She started screenshotting everything Finton posted. She dug into his past and found out he’d spent time in prison for assault and robbery and seemed to have adopted radical views behind bars. She kept watching. And as spring turned to summer, Finton’s posts got even darker. That’s when she called the FBI.

What happened next reads like a movie script, except more dramatic and all true. Federal authorities set up a sting operation that resulted in Finton getting into a van he thought was rigged with nearly one ton of explosives. He told his accomplice, in reality an undercover FBI informant, that the blast would be a “historic occasion.” He parked the van outside a federal office building in Springfield, Illinois, where hundreds of people worked. And then, from a few blocks away, he made a call that he thought would trigger the explosion. When nothing happened, he called again.

It could have been one more mass-casualty event on our grim, ever-lengthening list. Columbine. Orlando. Charleston. Gilroy. El Paso. Dayton. But it wasn’t. Because Finton was immediately swarmed by FBI agents and members of the Joint Terrorism Task Force. He was shackled, locked up, and indicted, eventually pleading guilty to one count of attempted use of a weapon of mass destruction against property owned by the United States. He’s now serving 28 years in federal prison.

There were plenty of news articles about Finton’s arrest, but you won’t find her name in any of them. Instead, in reports about her cases, you’ll see words like “tip,” “alerted,” “uncovered.” Words that basically mean her. Even the existence of her work has been largely a mystery. At least, until now.

This was the plan: For 96 hours, I’d disappear. No one could know where I was going—not my editor, not my husband, not my mom. I’d heard about the Savant from one of her colleagues at the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), where she works closely with law enforcement agencies. After several weeks of discussion, she’d agreed to speak with me only if I promised to withhold major details, including her location and exactly how she does her work. Two weeks before I met her, I still didn’t know her name. One week out, I bought a plane ticket that would take me to a small town in the U.S. (I can’t even say which region.) When my flight departed, I had no direct contact information for her, just the cell number of one of her handlers.

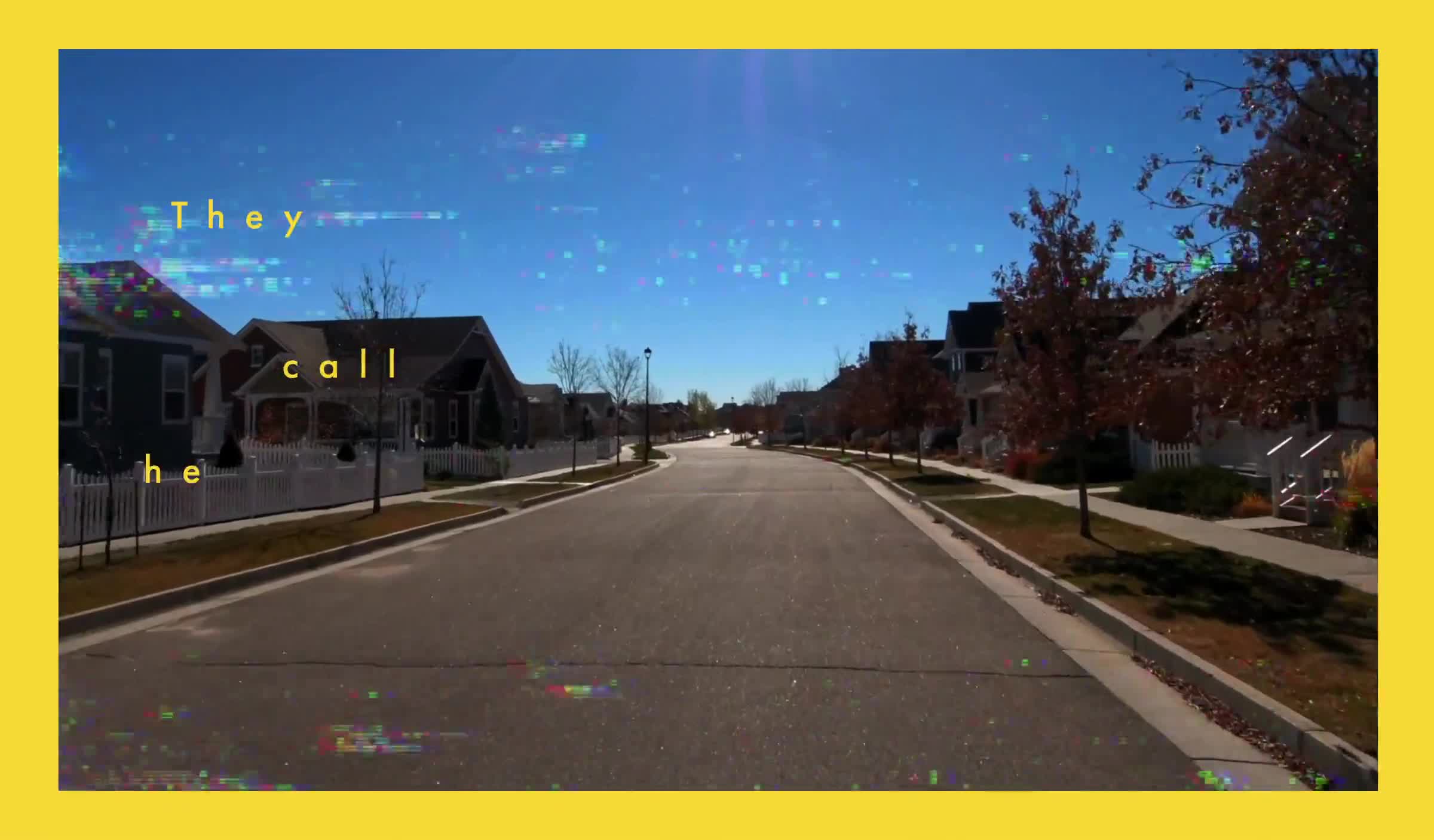

What I can reveal: Her house is a six-song-playlist’s drive outside of town. When I land on a Monday morning, I head north and west into a flat horizon in a rented silver Kia, passing a Target and a Texas Roadhouse. One of the nation’s premier investigators of extremism, hidden here amid the capitalist camouflage and exurban sprawl. I end up in a development for families on their way up: three-car garages, lawn crews, giant trampolines. The brown and powder-brown houses work hard to distinguish themselves from one another—a fountain in the front yard here, an orange wreath on the door there. Everything blends and blurs together; nothing stands out. This is the point.

I pull into a concrete driveway with a slight upward slope. The house has stone siding and a matching shed that sits to one side like a life-size dollhouse (her woodworking shop, I later learn). It’s the type of place you’d think belongs to someone with no secrets, the blinds wide open for anyone to look inside.

She answers the door herself.

She’s wearing a gray T-shirt, jeans, black boots, gold hoop earrings. Her height, her brown hair—it’s all normal, unremarkable. She looks how she looks, which is not like a top secret agent hunting murderous internet villains but also not not like one. She projects a low-key confidence that makes me feel like she could put me in a headlock (and she could, she will later admit, although “that wouldn’t be my first choice”). She tells me to call her K, based on a childhood nickname, and gives me a handshake-slash-hug. “I’m sure they told you I didn’t really want to do this,” she says.

She has a guardedness about her but laughs easily. “I hope you like dogs!” she says as hers yip at my feet. (I don’t, actually, but I lie, then immediately worry she can tell.)

We take a seat at her tawny-colored dining room table (she made it by hand). It’s here, amid stacks of bills, sticky breakfast dishes, and tropical vacation photos of her, her husband, and their kid, that K spends her days and nights infiltrating the angriest extremist networks in the country. Her hours are all the time; hate doesn’t sign off at 5 p.m. Her job, i.e., to stop potential mass murderers from carrying out their plots, used to mean tracking domestic terrorists like Finton. But lately, K’s focus has been pulled toward the alt-right, a younger, more misogynistic version of the white supremacist movement that’s converting a new generation on message boards and social media. She is tracking the men who hate women. And they’re so dangerous that most of her family and friends don’t even know what she does. “I just tell them I’m a researcher on domestic terrorism,” she says. “I think they assume I work for a think tank.”

Her life depends on her anonymity. It’s what allows her to exercise outside during the brightest bits of day and to shop for groceries without looking over her shoulder. She maintains such a low profile—no personal social media, zero selfies floating around on the internet (trust me, I looked)—that her biggest claim to fame in her cul-de-sac is that she chased off a guy who was grifting everyone’s Wi-Fi.

We move to her home office, where she pulls a plaque out of a drawer. It’s a photo and a framed letter from then–FBI director Robert Mueller that says, in part, “We are so grateful for the good work—and the good—you do.” It’s proof that the people who need to know know.

Studying behavior to predict what people will do next is not a new job. The FBI has employed profilers like K for years to help them catch serial killers and repeat rapists. But in the age of internet radicalization, it’s more important than ever to determine who is actively plotting mass killings versus just fetishizing them online. K is the best of the best at seeing the difference.

And of course, misogyny is having a devastatingly proud moment. “We’ve never really seen violent hate being directed at women like we are now, in the same way that it has been for Black people and Jews,” says Heidi Beirich, director of the Intelligence Project at the Southern Poverty Law Center.

To join a cult of angry men, you used to have to show up in a field in the middle of the night. You had to know someone, get a tattoo, shave your head. Now you just have to click around on a computer, anonymously if you want to. And scary numbers of men do. The ADL estimates that tens of thousands of alt-right members have popped up in the past few years. There are the incels (involuntary celibates), who are angry at women for not sleeping with them. There are pickup artists, or PUAs, who believe in manipulating women to have sex. There’s the Red Pill community, which preaches, among other things, that women have it better, so much better, than men. “If someone is lonely and connects with one of these groups, taking on the ideological beliefs of the group happens almost subconsciously,” says Michael J. Williams, PhD, a researcher who studies how to counter violent extremism. “The ability to recruit hate is more widespread than ever before. It’s far easier and faster.”

Meaning, these guys aren’t just trolls in basements—they’re people you probably know. Beirich calls them “millennial misogynists.” K says many are college-educated and articulate. They have day jobs and Tinder accounts. In the fall of 2017, white supremacist propaganda on college campuses more than tripled from the previous year, according to ADL data. No wonder, per the FBI, that hate crimes rose about 17 percent too. (This number is probably even a vast undercount, since hate crimes are notoriously underreported.)

Modern “male supremacy,” as the experts now call it, actually dates back to the 1970s, when men’s rights activists came about as a reaction to women’s liberation, explains Jessica Reaves, editorial director for the ADL’s Center on Extremism. This time, it’s not just feminism to blame—it’s Donald Trump. I didn’t say it. Nearly every expert I talked to did. “The 2016 campaign energized misogynistic groups,” says Reaves. “They heard very powerful men talking about women in a way we had never seen before in public.”

Many of today’s extremists hide their radical views under the guise of boy-next-door preppy looks and organize activities, like all-male hikes, to appear mainstream. “They have a product they want to sell and that product is hate,” says K. “When you see a bunch of normal-looking guys, you think, How bad could it be? But violent men don’t have to look any different from kind men.” Some of the ones K tracks post pictures with their kids and pets amid their calls for mass violence.

On sites like Gab, Reddit, 4chan, 8chan, and VK, the new white supremacists and misogynists hatch conspiracy theories that take off on Twitter and make it on fake news sites like InfoWars and even occasionally Fox News. They serve up “constant peer pressure to do something criminal,” says K. They turn hate speech into hate crimes:

Your girl broke up with you.

It must have been her fault.

She’s kind of a bitch.

Rape her.

End her.

It was this kind of dangerous thinking that galvanized Elliot Rodger, 22, an incel who in 2014 killed 6 people and wounded 14 others in Isla Vista, California; Alek Minassian, 25, another self-described incel, drove a van into a sidewalk full of people in Toronto in 2018 and killed 8 women and 2 men, injuring 16 others. Many of the other men behind large-scale recent murders have a history of violence toward women, per the International Center for Research on Women. The Parkland shooter was allegedly abusive to his ex-girlfriend. The Orlando nightclub shooter, the Texas church shooter, the California bar shooter—all reportedly violent toward women.

In other words, this isn’t a powder keg waiting to explode. It’s been exploding for years.

In March, K nailed 30-year-old Corbin Kauffman of Lehighton, Pennsylvania, who had posted tasteless memes and murderous threats on a fringe social media site frequented by members of the alt-right. His Twitter bio read: “One of the extremist WN [white nationalists] that CNN warned you about.” He’d posted a video of himself, a knife in his lap, speaking in an amped-up cartoonish voice about how he wanted to commit hate crimes. Before he could follow through, K had the FBI at his door. He’s now facing up to five years in prison.

K goes to her computer—the same one she uses to search for weeknight chicken recipes and advice on how to cut bangs. Suddenly, I’m looking at a picture of an arm tattoo in which Donald Trump is positioned doggy-style behind Hillary Clinton, his body thrusting, while she appears wide-eyed and terrified. It’s inked in black, permanent.

I see a riled-up thread in which men are arguing against women’s right to vote. A streaming video in which a man is flipping a switchblade. An illustration of a nude woman straddling a wood beam with her feet weighed down, alongside a quote that says, “[Christine Blasey] Ford needs to be curbstomped…torcher [sic] the pig”; a picture of a blindfolded naked woman with three men in masks standing behind her; posts about how sexually assaulting women should be legal; and posts like these:

“I #believewomen. I believe firmly they should shut the fuck up, quit wearing pants like a man, and GET THE FUCK BACK IN THE KITCHEN WHERE THEY BELONG.”

“I am 100% against hitting women I’ve never hit one myself. But a liberal feminist Dyke it’s not a woman and they have been green-lighted….”

“Men can’t wait for women to come around. Nature doesn’t work that way. We, as men, must regain our culture and take control.”

K is currently keeping close tabs on more than 1,000 men. She calls them her List. They’re right here on a spreadsheet, pages and pages of faces, light eyes and jelly-pocket cheeks, dark eyes and deeply sunken dimples, old skin and new.

One guy lives less than a mile from her. “I know their screen names, their real names, their fake names, when they change their names,” she says. Private accounts, alias accounts, multiple accounts—she knows. I can’t reveal her exact methods, but let’s just say anyone who is vocal online about his hate for women has likely chatted her up about his motorcycle or his family. In that way, these men are vulnerable, because they have to put themselves out there. The internet is their bullhorn, the best way they have to reach their disciples.

When she first started doing this, she did it in person. Once, a man caught her taking pictures at a gathering of white supremacists. She played it off, but her nerves were fried. Another time, she was jotting down some notes when a well-known extremist sat down right next to her. She remembers her heart beating so hard she could feel it in her fingertips. She slowly closed her notebook, terrified. What did he see?

Others in her field have been doxed, making them vulnerable to violence. One of her friends, who works in a similar job, told me she had to move after extremists firebombed a car in front of her house and ran her kids off the road. K does sometimes worry about the safety of her family. “Given the opportunity,” she says, “I’m sure they would come after me.”

So yeah, working from a computer has made her life easier. It’s also made it impossibly hard. When your territory is the internet, there’s a lot to sift through. Some words mean nothing; others mean people are about to die. And it isn’t always easy to find the words in the first place—the ones that belong to the person who will do the thing.

She points at a man on her screen who is so desperate for a Dylann Roof–style bowl cut that he’s photoshopped the round blond chop onto his own picture. “He really worries me,” she says. But for now, she’s holding off on reporting him, because he seems to lack the means to carry out a serious attack—he doesn’t yet own weapons. She stares at his page for another beat before clicking off.

Indeed, the line between bad and really bad is so thin that I can’t see it. K doesn’t always see it either. It’s more that she feels it. She explains: “You know that feeling you get when you’re about to get on an elevator and you get a sense that you shouldn’t because as the doors open, the person standing there gives you a bad vibe? Most people ignore that feeling and get on the elevator anyway. Me? I’ll wait for the next one.”

She’s tried to train others to do what she does. But she can’t “because when it comes to this feeling that I get when I just know this person is going to do something really terrible, I’m always like, Huh, how do I know that?”

She got the feeling last year from Dakota Reed, 20, of Washington state, an alt-righter who had posted a picture of himself in a mask pointing an assault rifle at the camera and had threatened to kill Jews. “I started tracking him and found multiple Facebook profiles where he was using different names and posting images of weapons,” says K. Law enforcement ultimately seized a cache of guns; he was charged with malicious harassment and making bomb threats and is currently serving a one-year sentence. (When investigators asked him why he targeted Jews, he reportedly said, “I’ve had girls like them over me.”)

When I ask Oren Segal, the director of the ADL’s Center on Extremism, if there are other people like K, he tells me there are other people who do what she does but no one like her. Because it’s not just her intuition—it’s that she literally never forgets a face. Once she encounters a hateful man online, “she remembers their name and everything about them,” says the friend who works in a similar field. “She’s got this phenomenal ability.”

After Charlottesville’s infamous Unite the Right rally in 2017, at which Heather Heyer was killed by a white nationalist, the authorities struggled to determine which extremists had been present. K identified 305 of them from pictures and video floating around on the internet. Some were charged with crimes. Others are now being monitored by law enforcement.

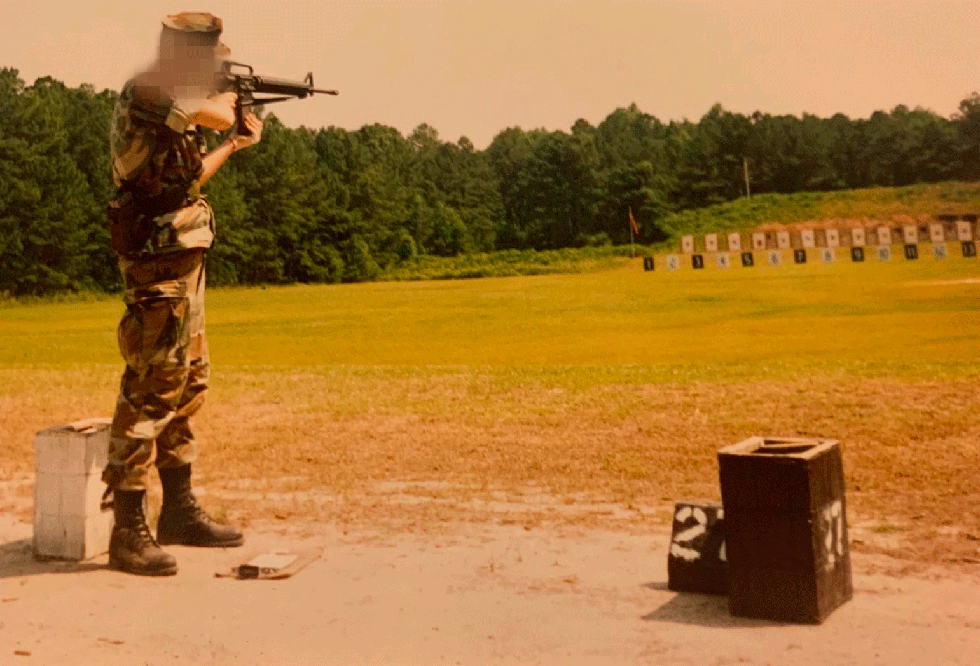

She grew up poor, in a trailer she shared with her parents and two older siblings, where buckets caught rain that came through holes in the roof. She rode the bench on her high school basketball team and played drums in the band. She was the last person anyone would have guessed would become a deep-cover investigator. It happened kind of accidentally, after she enrolled in the Marine Corps so she could afford college.

K was a good marine—focused. This despite all the men trying to get a peek at her during their 10-minute shower time on the base in Korea, where she was one of few women. A superior on base made jokes about killing his wife. Once, when he grabbed K in a sexual way, she clocked him. “He was wearing a flight suit that had all these pockets full of crap, so unfortunately, when I hit him, I actually hit something in his pocket,” she recalls. “I thought I broke my hand.”

“If you touch me, I’ll knock you out,” she told him. She was 19. He never bothered her again.

When she transferred to a base back in the U.S., she started night school and got a degree in justice and public safety. She became a police officer, going undercover as a sex worker or desperate druggie looking for a hit. “I had this piece-of-crap pickup truck with a baby seat in the front that had a camera in it,” says K. She got hooked too, on the adrenaline. “The chase of getting the bad guy? Oh, man, that feels good.”

Eventually, K took a job working for a state-run agency that reinvestigated capital-murder cases. This required her to meet with death-row inmates, Clarice Starling–style, alone in a small box-shaped room with nothing but stale air and a cold table between them. The gig was a master class on staying stoic in the face of evil. One guy recounted his crimes “in a tone someone might use to talk about a trip to the park,” recalls K. “He had stabbed a woman to death and wanted to rape her but told me he couldn’t because she was too slippery with blood. So he went and got her granddaughter. This time, he raped her first and then killed her.” K pauses. “If you freak out, they’ll stop talking,” she says. “So I would just nod, listen, and keep my face devoid of a reaction.”

Only one man ever got aggressive: “He told me he could throw me 100 feet, stood up, and shoved the table at me. He had killed a woman with a hammer.”

You’d think she would be angry at men after all this. But at one point, she tells me she doesn’t even consider herself a feminist. “There are shitty men and there are shitty women,” she says with a shrug. (It’s just that shitty women often aren’t the ones plotting to blow people up.)

Still, after her stint on murderers’ row, it all started to weigh on her. She’d had her kid by that point and needed a break. She tried briefly to become an artist, but that lasted three months, until she learned that the ADL was looking for someone to monitor extremist groups. The job would require going head-to-head with some of the worst men in the world. K knew she could do it, because she’d already done it for years. And to be honest, she kind of missed it.

A few weeks after my visit, I get an email: “He seems to fit squarely into the incel category,” writes K. The “he” is a 40-year-old white man who walked into a yoga studio in Tallahassee, Florida, and shot six women, killing two. A self-proclaimed misogynist who’d called women “whores” on YouTube and sang about wanting to “blow off” the head of a “cunt” on SoundCloud, he’d been arrested twice for groping.

K hadn’t had him on her List. The El Paso shooter wasn’t there either. “When I miss something, I feel terrible. It’s heartbreaking, devastating,” she says. Her entire career has taught her to be good at compartmentalizing—at functioning in the world despite what she knows. But when she feels responsible for not catching a murderer, “it just makes me feel exhausted, angry, sad, depleted. It takes a few days to recover mentally.”

It’s one of the reasons she doesn’t really sleep anymore. “The euphoria among extremists right now is really depressing,” she says. “I’ve never felt hopeless until the past 18 months.” Her work is “just a drop in the ocean,” she says. “I’m stretched thin trying to stay on top of it all.”

She tells me about one of the deeply troubling guys she’s been following lately, who posts rants about how he won’t let his wife watch television because it makes her too “feminist.” He shares degrading photos of naked women and fantasizes about electrocuting them—and seriously hurting others too. He recently hinted that these don’t need to stay fantasies.

He thinks he can get away with it.

He, at least, is wrong.