Here, I’ll catch you up.

“Americans ages 20 to 24 are so sexually inactive that it practically boggles the mind.” That was Bustle in 2016.

Millennials and Gen Z “are having sex less often than any previous generation,” according to the New York Times in 2017.

“Today’s young adults are on track to have fewer sex partners than members of the two preceding generations,” wrote The Atlantic last year in a cover story titled “The Sex Recession.”

Then just this past March, the Washington Post shrieked about the “Great American Sex Drought,” adding that “you can blame young people for this dry spell.” (We’ve already been blamed for nut milk and the Kardashians, so sure, why not?)

The most okay, whatever headlines pit our new notoriety as sexless against our old rap as sluts. “Study Dashes Millennials’ Reputation as Hookup Generation,” one website crowed.

(It’s possible you missed all this noise because, I don’t know, you were too busy having sex.)

But the thing is: They’re wrong. The data behind these headlines is inadequate and doesn’t even really back up the grim tale they’re peddling in the first place. Nor does it take into account millennials’ own opinions about our sex lives (because no one asked us). Instead, the closer you look at the myth of the “sex recession,” the less it seems like a recession at all.

Yeah, we’re doing sex differently (the numbers don’t consider non-penetrative sex, vibrators, porn, and the fallout from #MeToo). But what’s actually happening is less about some overhyped drop in sexual frequency than “the rise of sexual intelligence,” according to Helen Fisher, PhD, a biological anthropologist and senior research fellow at The Kinsey Institute. Fisher, who was quoted in some of the recession stories, says she finds the headlines “ridiculous” and the panic overblown.

We millennials happen to know we’re killing it in the bedroom (and in our cars, and in our showers, and on our couches), and we want credit for it (we are millennials, after all).

First: about those numbers everyone’s been so obsessed with. A lot of the “sex recession” panic can be traced to data from something called the General Social Survey (GSS). It’s a long-term study that helps politicians and researchers take America’s temperature on a wide range of political and cultural issues. It’s not a sex survey, but amid questions on wealth inequality and religion, it does ask a few basic bonking Qs, including “How many sex partners have you had in the past 12 months?” and “About how often did you have sex during the past 12 months?” It doesn’t define “sex” in these questions or ask whether you’re having good sex or even whether you’re cool with the amount of sex you’re having. But since it has been conducted for decades, it allows researchers to compare different generations over time.

Here are some of the things it found: Between 1989 and 1994, 18- to 29-year-olds reported having sex an estimated 81.29 times a year, according to an influential 2016 analysis of the data by Jean Twenge, PhD, a professor of psychology at San Diego State University and author of iGen. But by 2010 to 2014, that figure had dropped to—wait for it—78.5 times. That’s just 2.79 fewer romps a year. It’s 6.5 a month. And it’s still more than any other age-group’s estimated number. So even though we’re having a whole lotta sex, we’re getting scolded because it’s slightly less than the olds said they had at our age.

Also, since the GSS doesn’t define “sex,” nobody knows if millennial respondents counted oral, solo, non-penis-involving, or any other non-penetrative play in their tallies. “The question doesn’t say ‘intercourse.’ It doesn’t go into oral sex or sex-toy use or any of those things,” says Debby Herbenick, PhD, a research scientist and professor at the Indiana University School of Public Health. This really matters, since millennials are more sexually experimental than other generations, according to multiple studies.

Not to mention that the GSS is primarily conducted face-to-face. How honest (or even accurate?) would you be if a stranger asked you how much sex you’re having, in the middle of quizzing you about your thoughts on free speech and legalized weed? (Twenge, for her part, admits the GSS questions are limited but says she uses it because of its sample size and longevity. She also, btw, told me that “sex recession” is “not my phrase.”)

Anyway, “our definitions are expanding,” insists Justin Lehmiller, PhD, a research fellow at the famed Kinsey Institute and author of the book Tell Me What You Want. “It’s not that we’re necessarily having less sexual contact overall, we’re just having different kinds of sexual contact than have traditionally been measured.” In a January article, Lehmiller called these changes a revolution.

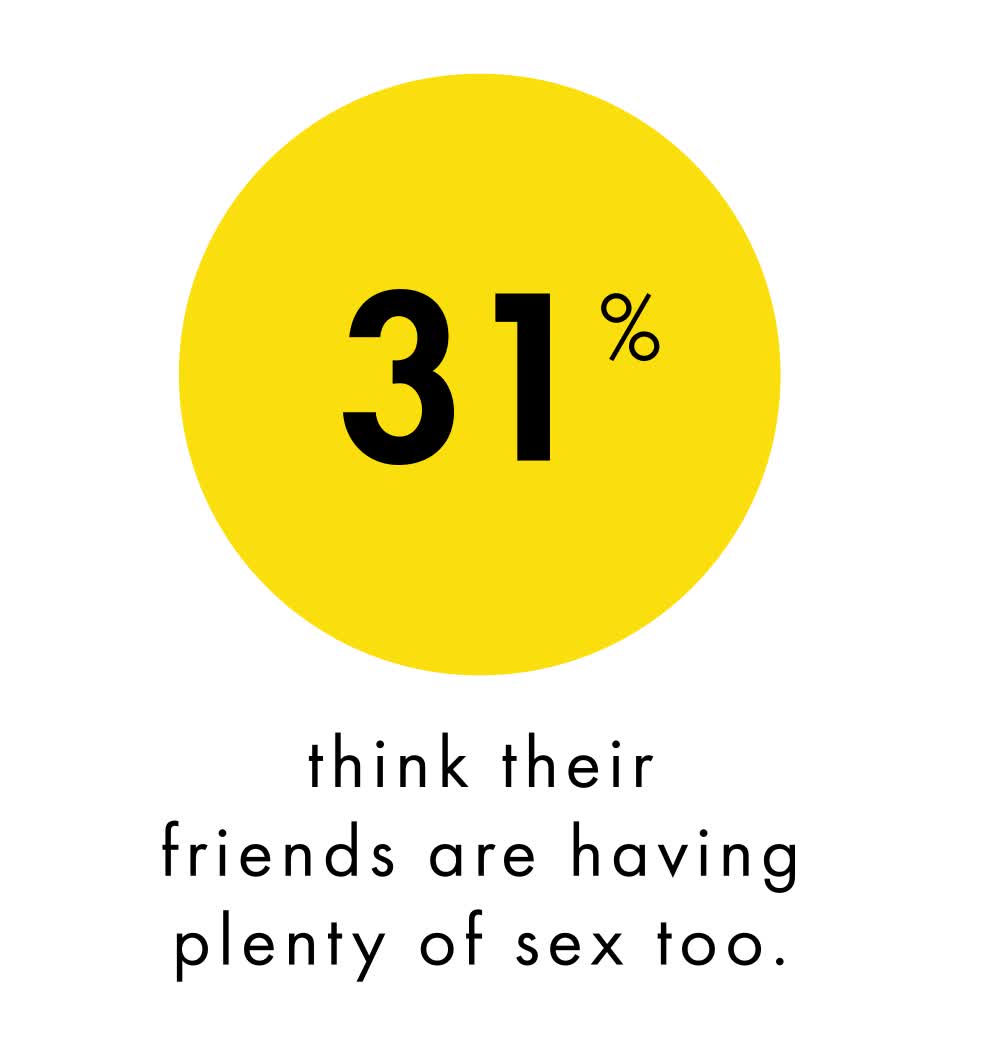

Data that questions the “sex recession” plotline isn’t even all that hard to find. In a 2019 survey of 2,000 Gen Z and millennial adults by Skyn Condoms, we reported having sex an average of nine times per month. The average age at which teens lose their virginity has held steady at 17 for two decades, according to the CDC (“If younger adults really were having a lot less sex, you’d probably see the average age of first sex increasing,” explains Lehmiller). What all this points to is that sexual frequency is a random and incomplete way to measure a generation’s sexual vibrancy—and a really good way to miss the big picture.

When you talk to actual millennials, a totally different and way more positive story comes into focus—one that’s less about shaming or celibacy than it is about agency and abundance. We’re a generation that favors artisanal everything. Why would we settle for basic sex?

“It’s not like we’re less horny,” says Remy Kassimir, 29, host of the How Cum podcast that chronicles her journey toward her first orgasm. (Spoiler alert: She came!) “We’re not, like, robots. We’re just being smarter about stuff and asking, ‘Is this going to be worth my time and emotion?’” Rather than risk a bad hookup or unwise emotional entanglement, she says, “wouldn’t it just be nicer to go home to my Womanizer and get on with my day?”

Amanda, 28, says she’s tried it all in the bedroom: BDSM (she’s been tied up), anal (not her thing), sex toys (the Magic Wand, obviously), and watching porn with her partners. At this point, she’s been with close to 50 people. But for her, it’s more about how well she’s doing it. “I have to feel a connection with someone, even if it’s as simple as the fact that we make each other laugh,” she says. “If we can communicate effectively, almost as friends, that just makes the sex better.”

Herbenick runs the National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior, an almost-yearly poll that asks explicit and nuanced questions about sexual orientation and how recently people have done stuff like toe sucking and spanking. Her data does show a slight downtick in sexual frequency, but it also shows signs that pleasure is increasing over time. And Match’s 2016 Singles in America survey of 5,500 people, for which Fisher is the chief scientific adviser, found that millennials are 40 times more likely than other generations to believe that an emotional connection makes sex better.

“This is a generation, more than any other generation, that can really fuse the relational with the recreational to create sex that feels intimate, emotional, and connected, in which pleasure is really front and center,” says psychotherapist Ian Kerner, PhD, a sex counselor in New York City and author of the book She Comes First. Or as Amanda puts it, “I’m not one of those people who’s satisfied with not getting off.”

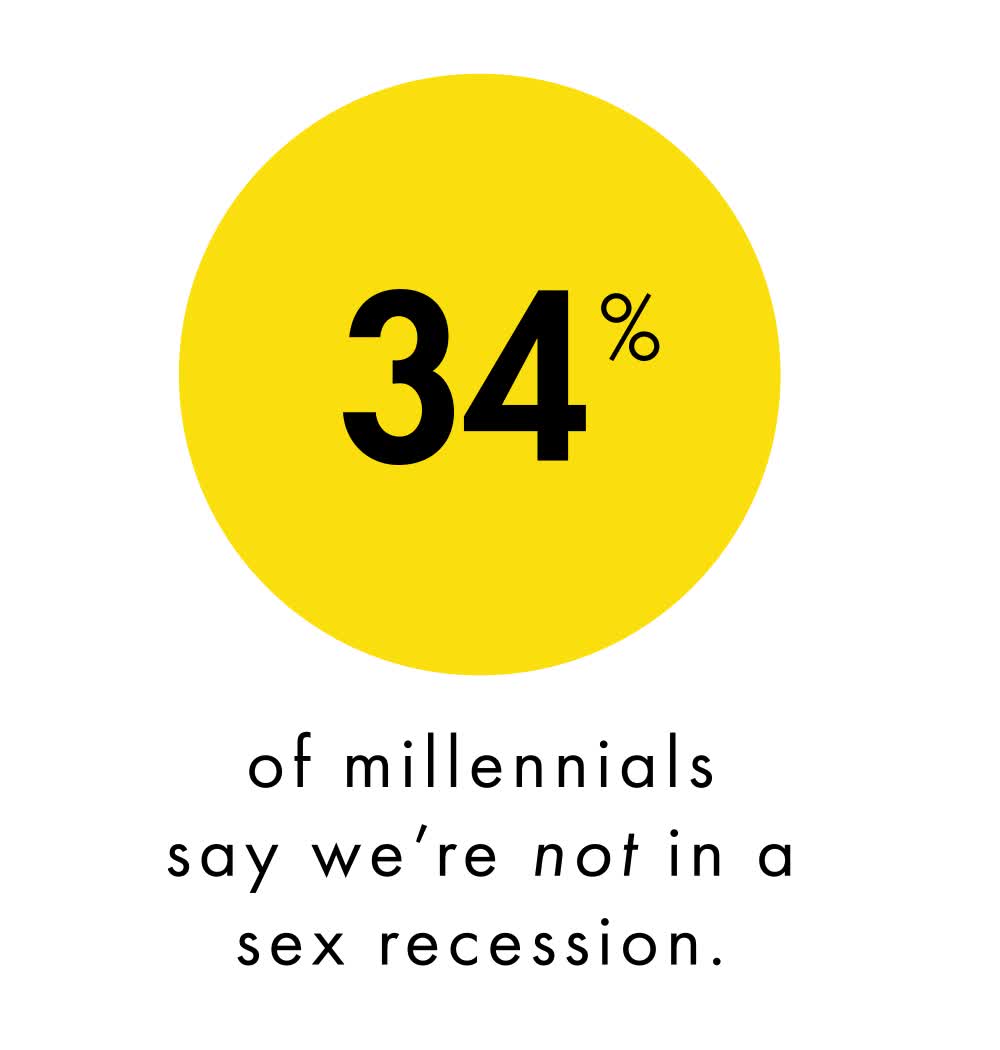

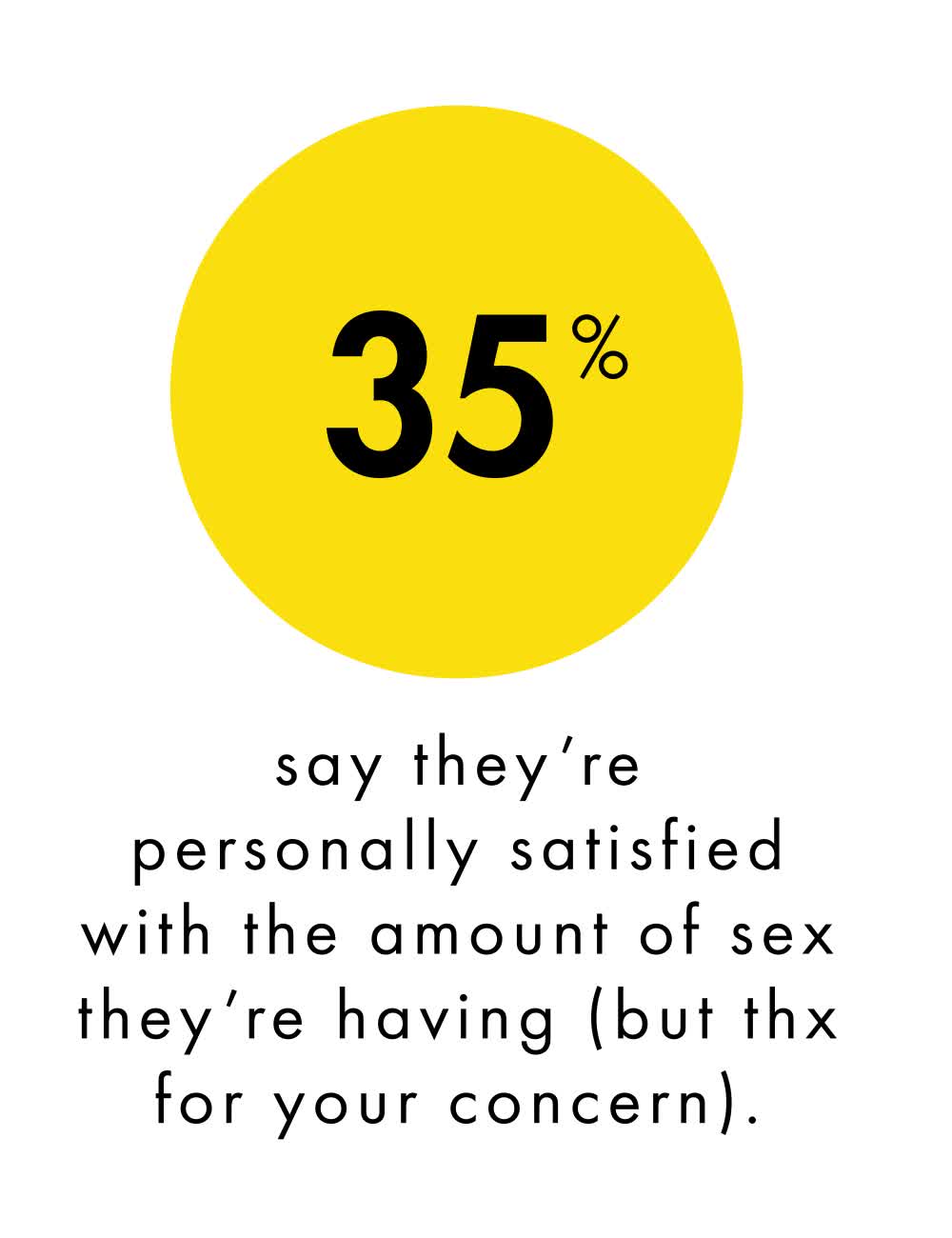

RT! RT! The real TL;DR on our generation is that we’re having sex that is experimental but also pleasurable and meaningful. We confirmed it ourselves in our survey, in which literally almost every respondent said they value quality over quantity when it comes to sex. They were also overwhelmingly satisfied with their own sex lives, a notion that has not been explored in all the alarmist articles.

Because the truth is, regardless of how often we’re having sex, we have embraced fluidity, dismantled stigmas, and freed ourselves to pursue the sex we actually want. Gallup research shows that more youngs than ever before identify as LGBTQ+. “Younger people are much more open to casting off older and more traditional labels in favor of something that fits their ideologies and preferences,” says David Frederick, PhD, an associate professor of psychology at Chapman University. This kind of acceptance (from ourselves and also others) is the key to good sex: Feelings of identity pride are linked to bedroom fulfillment, according to research in the journal Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity.

Amy Boyajian, 28, a former sex worker who cofounded Wild Flower, a millennial-focused online sex shop, recalls rolling their eyes when they read the Atlantic piece. “It was kind of missing the point on where millennials are with sex nowadays,” they say. “The interest is there, it’s just less traditional.”

Of course, it’s impossible to talk about sex in 2019 without talking about #MeToo, which is the most seismic meteor to hit the landscape of intimate relationships in decades. When you think of all the stories we’ve heard since it exploded in 2017 about bad sex, coerced sex, harassment, and rape, the idea that millennials are mostly having the sex we really want to have seems even less like a sad dry spell and more like mass empowerment.

While there isn’t any hard data yet on the effects of #MeToo, Herbenick points out that we were already more confident than our predecessors at turning down potentially bad sex. “People have had to start thinking about what it means to have sex that feels good,” she says. “Some are really trying to take the affirmative-consent approach, where less of the sex they’re having is in that murky area.” Could this slow things down? Yeah. But that’s something to celebrate, not pity. “If I’m not having sex at the moment, it’s because I’m being a little bit more choosy,” says Amanda. “I’m more confident. I know what I want. And the people I am having sex with, they’re more important to me.”

Even before the Harvey Weinstein story broke, a 2015 study found that the idea of “owing” a man sex just because he paid for a date was already antique. Only 22 percent of women ages 18 to 25 said that helping pay the tab made them feel less pressure to have sex; that number jumped to 46 percent among women ages 56 to 65 (yikes). “I’m a Gen Xer, and back then, you didn’t feel as empowered to say no,” says Kristie Overstreet, PhD, a psychotherapist and clinical sexologist who works with millennials in Huntington Beach, California.

Maybe most of all, #MeToo challenges the idea that we can measure our sex lives by anything other than our own generational values and self-reported satisfaction.

Millennials are still doing it—and doing it often. It’s possible we’re going in less for penetration and more for the other stuff. We’re using all the toys to make sure we come. We’re sticking to partners we really like. We’re not limiting ourselves with labels. And most important, we don’t think this is a sad story at all.

When I call up Mary Jane Minkin, MD, a clinical professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Yale School of Medicine, to get the opinion of a doctor who sees millennials all day in her classrooms and her medical practice, she laughs at the idea of a sex recession. “Wait, let me see if my business partner is here. I want to get another professional’s viewpoint,” Dr. Minkin says. She calls out to her office, “I have a question! I have Cosmo on the phone asking if millennials are having a lot less sex than previous generations.” A pause, a few mumbles, and then Dr. Minkin is back. “She’s making a face, shaking her head ‘no way,’” says Dr. Minkin. “The phrase she used was ‘fucking like bunnies.’”