It was 2017, deep into summer, when a popular high school cheerleader from the nice side of town was charged with killing an infant.

The county sheriff’s office arrested 18-year-old Brooke Skylar Richardson, claiming that after hiding her pregnancy, she gave birth, set fire to the baby, and buried it in her backyard. Skylar faced multiple felonies, including aggravated murder, involuntary manslaughter, child endangerment, and abuse of a corpse.

As a motive, prosecutor David Fornshell told the story of a teenager obsessed with projecting the perfect image. Skylar and her mom, as he painted them in a press conference, were consumed with “how things appeared to the outside world.” And he dropped this detail to reporters: Skylar had burned the baby, perhaps even while the newborn was still alive. Fornshell had little to go on—no medical proof—but the idea rocketed around Skylar’s conservative community anyway.

Former friends and classmates turned on Skylar. They pumped reporters full of gossip (“Skylar was the school slut,” “Skylar wrapped her stomach with cellophane to stop the baby from growing”). Some tiptoed onto the Richardsons’ lawn, their phones aimed and ready, hoping for a snapshot they could sell to the press. Even the hairdresser Skylar had been going to for years sat on a porch across the street taking pictures.

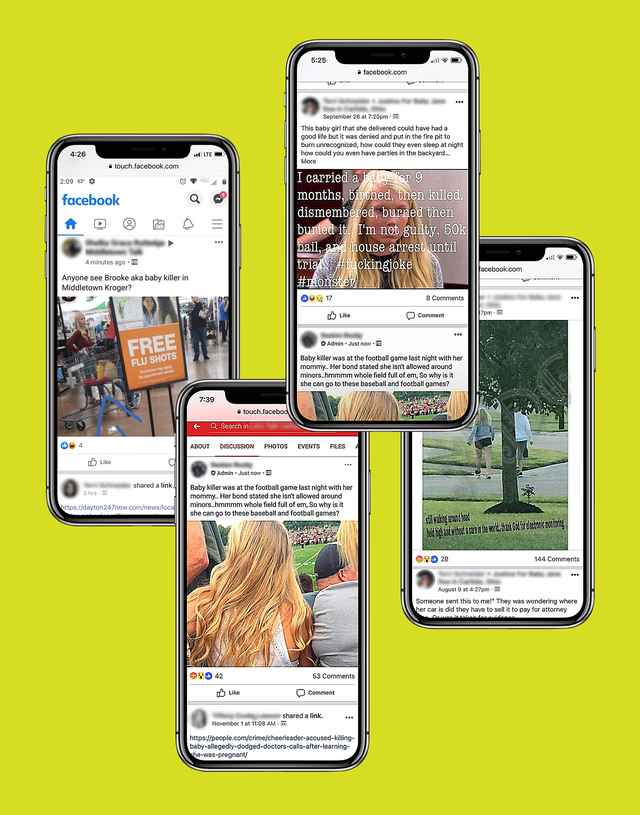

Then there were the Facebook groups. “Justice for Baby Jane Doe in Carlisle, Ohio,” and “Justice for Baby Carlisle” were where people obsessively tapped out their theories, “evidence,” and threats—posts suggested that justice would be to “burn Skylar alive” or “have her uterus ripped out” or that “she needs a bullet.”

And there were headlines like this: “Teen allegedly smashed newborn baby’s head, set her on fire.”

By the time the verdict came down this past fall establishing Skylar’s innocence, it hardly seemed to matter anymore. “I’ll straight bully this bitch the rest of her life,” one commenter said.

That was their version. This is Skylar’s:

On April 26, 2017, less than two weeks before senior prom, her mom, Kim, took Skylar to her first-ever gynecologist appointment. For years, her periods had been irregular—sometimes super heavy, sometimes super light, occasionally not at all, and, lately, sporadic spotting. Plus, Kim knew that Skylar had been engaging in “adult actions” with her then-boyfriend, Brandon. Skylar was months away from the rest of her life—she was headed to the University of Cincinnati to study psychology that fall. And Kim wanted to get her on the pill to avoid an unplanned pregnancy. “I only want you to reach your potential and not have any roadblocks,” Kim texted Skylar the day before the appointment.

Under chlorine-white fluorescent light, in a paper gown that ripped when she moved, Skylar listened as her ob-gyn, William Andrew, MD, told her she was about 32 weeks along. The pill wasn’t necessary. She was already pregnant. And well into her third trimester. One of her first thoughts: I can’t have a baby. Another: This can’t be true. She doesn’t deny that she was scared.

As Kim sat in the waiting room, Dr. Andrew urged Skylar to tell someone about the pregnancy. (He was bound by doctor-patient confidentiality.) But as she drove home with her mom, Skylar didn’t. If she could, this is the moment she would rewind to. “My biggest regret is not having the strength to tell someone that I was pregnant,” she exclusively tells Cosmo. “I wish I would have done it differently. I’m plagued by guilt every day for not telling someone.”

It’s just that it was prom. She already had a cherry-red dress and a date and a group text full of plans. And for a second, focusing on something else felt...good. Skylar resolved to tell Kim that she was pregnant, after the dance.

On May 5, Skylar and Brandon posed for pictures at the Richardsons’ house before heading off to prom. Looking at the photos now, you can see a bump, but at the time, Skylar’s friends and family just thought she was finally overcoming her eating disorders—everyone knew she’d struggled with anorexia and bulimia since sixth grade. To them, she looked “curvy and radiant.”

Skylar danced but didn’t drink. And she didn’t stay long—she wasn’t feeling well and had Brandon take her home early. A kiss good night and the big night was over.

The next day, she had intense stomach cramps that only got worse. By nighttime, they were so bad that she nearly collapsed when she tried to stand up. She didn’t think she was in labor—she thought she had months left in her pregnancy. She went to the bathroom, sat on the toilet, and felt “that something needed to come out.”

What came out was a baby girl who was shockingly white. Skylar tried to catch her, but she couldn’t. The baby was so slippery, wet with blood and the mucus-y fluids of childbirth. She lifted the small body from the water and is firm on this: The baby was dead. She never cried or moved or opened her eyes. The umbilical cord wasn’t even attached. Skylar pressed her fingers to the baby’s chest, as if searching for a button to switch on her heartbeat. “I hoped she would start coming alive,” she later told police.

Skylar swaddled the baby in a towel and sobbed. She was bleeding, badly, all over the cream-colored tile. Her parents were asleep downstairs, and her younger brother, Jackson, then 15, was just one room over, but it felt devastatingly impossible to tell anyone now. Slumped against the bathtub, the lifeless baby in her arms, she decided there was only one thing she could do: bury her.

In the dark, hastily dressed, she got her mom’s small garden trowel from the garage and dug a grave in the backyard. It was shallow—Skylar “wasn’t strong enough” to make it deeper because she was in a lot of pain. A name, she thought. The baby needs a name. “I decided to call her Annabelle. I didn’t know anyone with that name, so I knew whenever I heard it, it would remind me of my baby girl.” And then she unfolded the towel Annabelle was wrapped in, placed her in the ground, and covered her with a layer of dirt. Before leaving, she put pink flowers on the grave.

But then...what if someone had gotten up while she was outside? Stumbled into the bloody bathroom? There were many nights that Jackson had heard the sounds of Skylar’s bulimia, as she heaved into the toilet. But back inside, everything was quiet. She cleaned up the bathroom, threw away the blood-soaked towel, and it was done.

The next morning, she went to school. Shock and denial carried her through the motions of her normal life—Skylar wouldn’t even tell anyone about that night until months later, in July, when she tried again to get birth control. This time, she saw a different doctor, Casey Boyce, MD, who had been tipped off by Dr. Andrew about Skylar’s pregnancy and questioned her about it. Skylar got so upset while explaining what had happened that staff outside the room could hear her sobbing. She told the doctor everything, never assuming she’d get in trouble for what she thought was a tragic accident. After all, as Skylar reiterates now, “I did not hurt, harm, or kill Annabelle.”

Skylar didn’t know that Dr. Boyce would alert authorities (physicians are required by state law to report any suspected instances of child abuse or neglect) or that two days later, she’d be called into the police station for questioning. With neither her parents nor an attorney present, Skylar sat in a small room and told police over and over again that she did not kill her baby. It seemed like the detectives believed her. One held her hand, and the other told her that her effort to bury the baby was “noble” and “the right thing.”

At the trial this past September, a sliver of Skylar sat at the front of the courtroom. Her clothes—a pink sweater, a pair of gray pants, other attorney-approved outfits—had to be pinned so they fit her frail frame. The stress of the two years leading up to this moment had made her eating disorders worse. She weighed less than 90 pounds.

From the moment she was charged, she had been living in what felt like a permanently paused state, put on house arrest and allowed to leave only to go to her attorney’s office or doctor’s visits (the terms were loosened eventually, but she still had to abide by a curfew). She should have been in a dorm, halfway finished with her college degree. Instead, the closest she got to a campus was FaceTime, when one of her close friends would tell her about her roommates and classes, the epic parties. She took the calls from her childhood bedroom.

“These things just happen—babies are stillborn— women shouldn’t be blamed for that,” says Ashley, who has known Skylar since middle school. “It’s sickening what they have done to her. I just try to keep it as normal as possible and be there for her as a friend.” Another longtime friend says Skylar told her that she “misses her baby.”

“I spent a lot of my time depressed,” Skylar says of those two years. “Every night, I would lie down and wish that I could have died in place of Annabelle.”

She deactivated social media and avoided reading about her case. Instead, she read novels (mostly mysteries), learned to cook and knit, and did chores. She got dressed and put on makeup every day, despite having nowhere to go. Even her porch was largely off-limits—too many gawkers outside.

An administrator for one of the Facebook groups often parked out there, swigging bottles of Coke, so she could capture Skylar content. “White SUV just pulled out of garage,” she wrote in one post. Before that, she uploaded Skylar’s mug shot with the line: “Gosh, I’m so excited, 25 weeks tell [sic] trial.” The post included eight laughing-face emojis.

“It was so hard to live knowing the truth but to have the whole world think otherwise,” Skylar says. “The people out there who hate me so much and wish horrible things upon me also do not know me.” Even now, as Skylar finally speaks about her experience, she knows plenty of people have plenty of expectations about how she should come across. Angry, maybe. Relieved. Repentant. Perhaps even philosophical about how everything happens for a reason. But currently, she is not well. She hasn’t slept—chest pains and panic keep her awake. She can’t eat. She admits she’s struggling and really, for the first time, processing it all—allowing herself to be a mom in mourning and not a murder suspect.

When the trial began, it largely hinged on what Skylar’s legal team said was a coerced confession. During a second interrogation, detectives told Skylar the same thing prosecutor Fornshell would later claim: They had evidence her baby had been burned. Skylar repeated 17 times that it wasn’t true, but when they suggested that Skylar was probably just trying to cremate the baby, “because that’s normal—it’s in the Bible,” she eventually gave in. It seemed like if she told the police what they wanted to hear, she would be allowed to go home. At the trial, the state’s own expert admitted there was no proof of burning. (Fornshell did not respond to Cosmo’s requests for comment or an interview.)

Skylar watched as her private text messages, photos, and search history were debated. She listened as prosecutors painted her as a selfish teen and asked her gynecologist deeply personal questions about her medical history. Had she brought up abortion, they wanted to know. The doctor confirmed she had not.

“Inside, I felt like I was dying,” Skylar says. “Very few things have been harder than having to listen to prosecutors allege horrible, unthinkable things of me and put countless photos of my daughter’s bones on a big screen.”

The 42-seat courtroom was small and always packed with people. Skylar’s family sat directly behind her, a rotating cast of her parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles. The majority of the space was taken up by national and local news media, except for a small area behind the prosecution. There sat Tracy Johnson, whose son, Trey, was proven through DNA to be the father of the baby (he and Skylar had dated for about three weeks, before she started dating Brandon; initially, Trey denied to authorities that he’d ever had sex with her, according to the sheriff’s office case summary). Tracy showed up daily with bags under her eyes and a box of tissues. Later, at the sentencing, she would address the court, saying, “Skylar’s selfish decision was not her only choice.”

Skyler sat silent through it all.

“I felt very disassociated, which is how I often cope,” she says. “I did as I was told, wore what I was told, stood up straight, and held my head high.”

The prosecution had offered Skylar a choice: In exchange for pleading guilty to the lesser felonies, the most serious charge of aggravated murder, which could carry a sentence of life without the possibility of parole, would be dropped. If she agreed, Skylar would face only up to 15 years in prison rather than life.

“It was appealing at first, but there was no way I could live with myself if I pleaded guilty to something I did not do,” Skylar says. “What scared me most about going to trial was knowing that based on media coverage, I was already seen as guilty.” (In a text to Cosmo, Skylar’s mom writes: “I was so scared I wanted to throw up when she turned it down. I am so proud of her strength. She risked life in prison to do the right thing.”)

After the eight-day trial, the jury took less than five hours to reach a verdict. Skylar stood, pale-faced, as the judge delivered the words that would change her life: not guilty. (For burying the body, she was found guilty on one count of abuse of a corpse and sentenced to three years’ probation.)

She broke down in tears. “I knew in my heart of hearts that I was innocent,” Skylar says.

And yet, to many, Skylar is still “Skylar the baby killer.” Where there used to be a few Facebook groups, there are now others with names like “Precious Little Baby That Never Had a Chance” filled with thousands of people. They remain active, months after the verdict. “I’m still living with a lot of fear,” Skylar says. “The past two years have been nothing short of a nightmare. After being constantly afraid and paranoid of everyone and everything around me, I’m having a hard time letting that go.”

Posts are a mix of memes that mock Skylar, stream-of-consciousness commentary on the case, and live-tracking Skylar’s movements. One included a picture of Skylar standing in a grocery store, a jug of orange juice in her cart, with the caption, “Anyone see Brooke aka baby killer in Middletown Kroger?” There’s also a photo of her in the bleachers at her brother’s football game floating around the internet; the person who snapped the pic was sitting so close to her that they could have reached out and touched her hair. There have even been death threats against Skylar and her family. Multiple administrators for the Facebook groups did not respond for comment, except for one, who said, “Go to hell.”

As Ashley describes it: “It’s a small community—nothing like this ever happens in Carlisle—and people love drama. They wanted the story to be as crazy as possible.” The scandal of it all, frankly, was fun. They saw it as their town’s Hollywood moment, with Skylar as the “new Casey Anthony” in what could be “a Lifetime movie.” It was addictive, watching the downfall of the pretty girl who used to drive around town in her white convertible, blonde hair blowing. Look at the Richardsons—they thought they were better than us.

Leaving the town that can’t stand the sight of her but also can’t look away isn’t, surprisingly, what Skylar wants though. She finds comfort in being surrounded by her support system (she still lives with her parents), especially her family and a close-knit circle of allies who fiercely rallied around her. “There’s no doubt in my mind that she didn’t do anything wrong,” says Skylar’s friend Annie. “She’s ready to move on and she deserves that. She’s a sweet person, not a monster.”

Plus, her job—the job that, she says, “saved my life”—is here. Soon after she was charged, she applied to more than 40 positions, but no one found her worthy of salting french fries or taking coffee orders. “I’m an extremely hard worker,” she says (one of her first jobs was at the Y daycare babysitting kids). “I knew it was only because of the charges against me.”

Her attorneys, father-and-son team Charlie H. and Charlie M. Rittgers, decided to bring her on board. She waters their plants, takes out the trash, and does other general office tasks. “Having the responsibility of a job has given me a purpose again,” she says. “Everyone treats me so kindly and with respect. It helped give me back some of the confidence I lacked.”

That’s critical, because Skylar is, in some ways, still fighting for her life. She recently spent time in treatment for her eating disorders and admits she has a long way to go in her recovery. “When I couldn’t control anything else in my life or situation, I could control my size and weight,” she explains. “I didn’t see much reason to take care of myself, so I tortured myself by starving and purging.” She’s also been diagnosed with mild PTSD and severe depression. There are nightmares and anxiety attacks and debilitating flashbacks. Is someone going to sneak into my room and take me so they can hurt me? is a thought she often has. She frequently sleeps in the living room. Kim says she’ll wake up in the middle of the night to find Skylar on the couch watching TV.

But Skylar made herself a promise, and she intends to keep it: “I said that if I could survive the trial, I would get all the help I needed. I want to make the best of my life and use my experiences to help in one way or another.” Eventually, Skylar says she hopes she’ll be an attorney for the Ohio Innocence Project. She’s signed up for paralegal classes at a community college that start in the spring semester. A reminder that right now isn’t forever.

In October, the family had a private memorial for Annabelle so they could bury her properly, in a plot far from town. “It is such a relief to know that Annabelle is now in her final resting spot,” Skylar says. “I visit every week.” Before leaving, she puts pink flowers on the grave.

Sonia Chopra is a freelance writer based in Cincinnati, Ohio. For twenty eight years, she has been a reporter, editor, blogger and a columnist. She's a correspondent for the Cincinnati Enquirer, and a stringer for the New York Times. Her work has appeared in Cosmopolitan, Teen Vogue, and various other outlets.