Alex (or maybe his name is Andrew or Jesse) brought you back to his place and things are totally on. His arms? Beefy. His make-out skills? Clutch. His hair? Like Zeus himself blow-dried it. Clothes are coming off and then, right at the crucial moment, he looks at you with eyes a color you’ve only ever seen before on tropical postcards and whispers slowly into your ear, “Don’t worry, babe. I’m on the pill.”

The idea that this scenario could be a reality (give or take a few details) has been looming for what feels like forever. Headlines have promised that long-term, reversible male birth control is *this close*. Then...nothing. It’s all started to feel like a cruel, elaborate joke. How can women have dozens of contraceptive options and men only have two: one-time-use condoms and permanent vasectomies?

As our investigation found, it depends on who you ask. Some scientists say killing millions of sperm is harder than dealing with one egg. Pharmaceutical companies tend to think it’s too risky to fund the development of something men won’t use (and women won’t trust them to take). Independent experts blame systemic sexism. Reproduction, they say, is still seen as strictly a “women’s issue.”

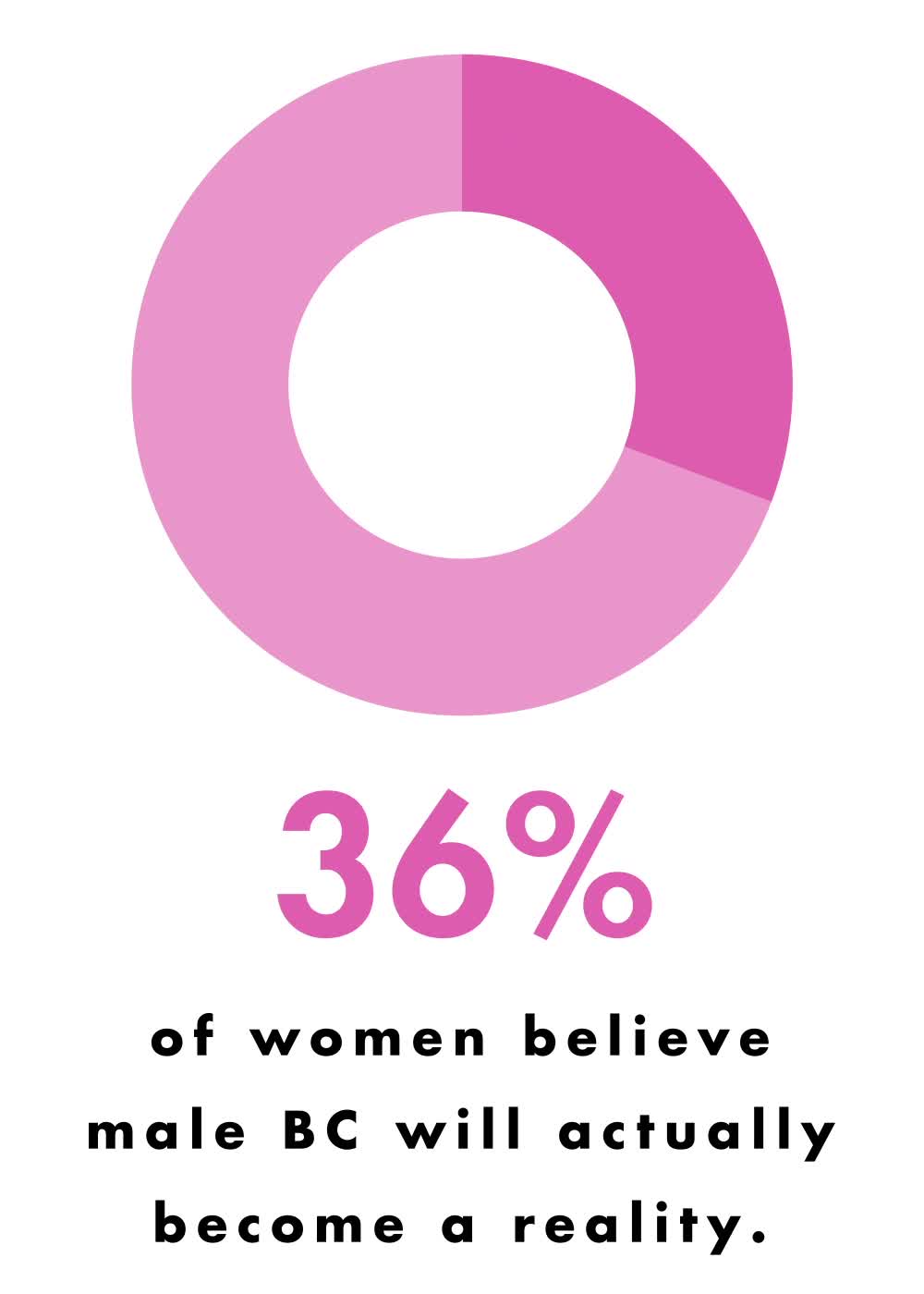

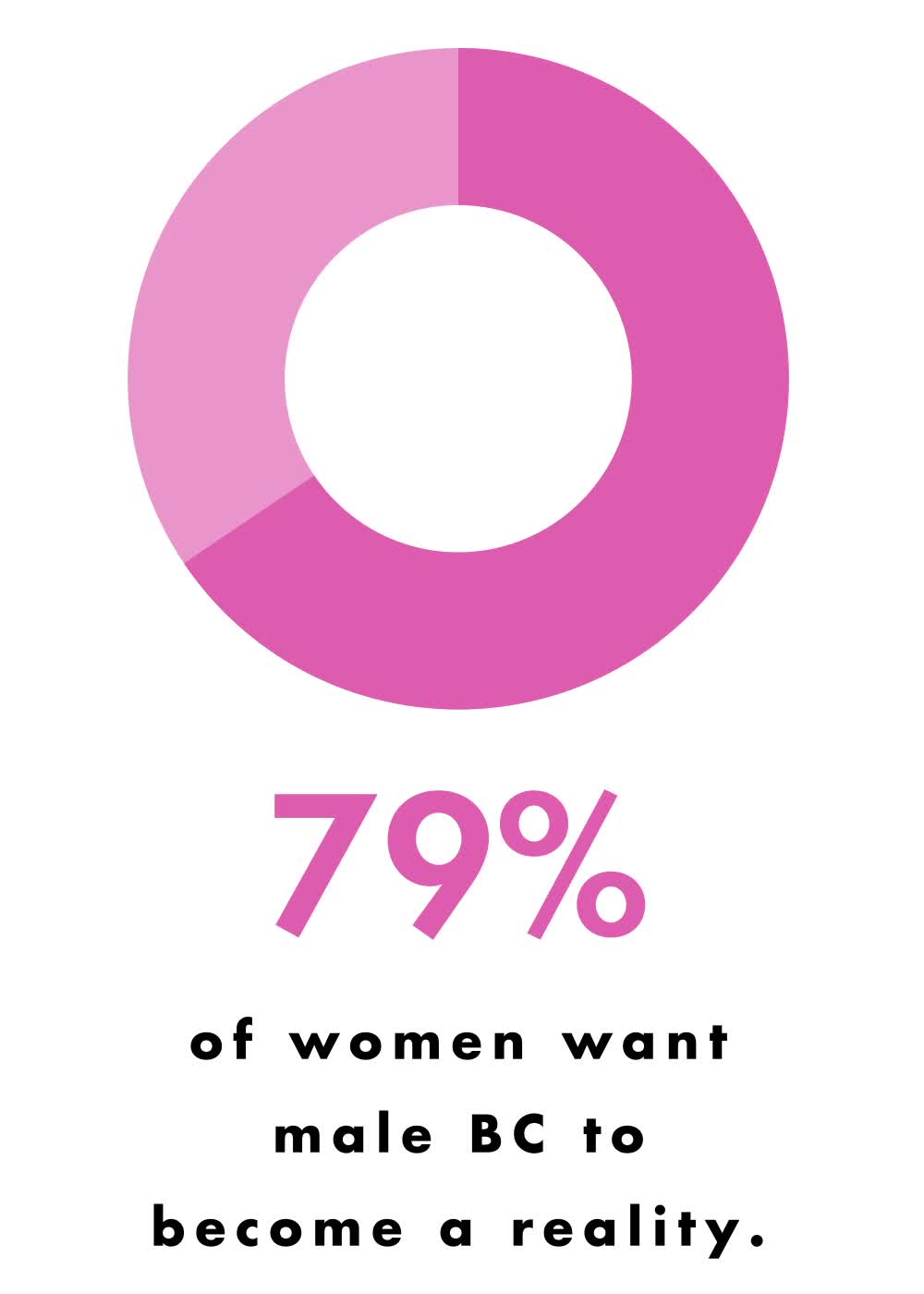

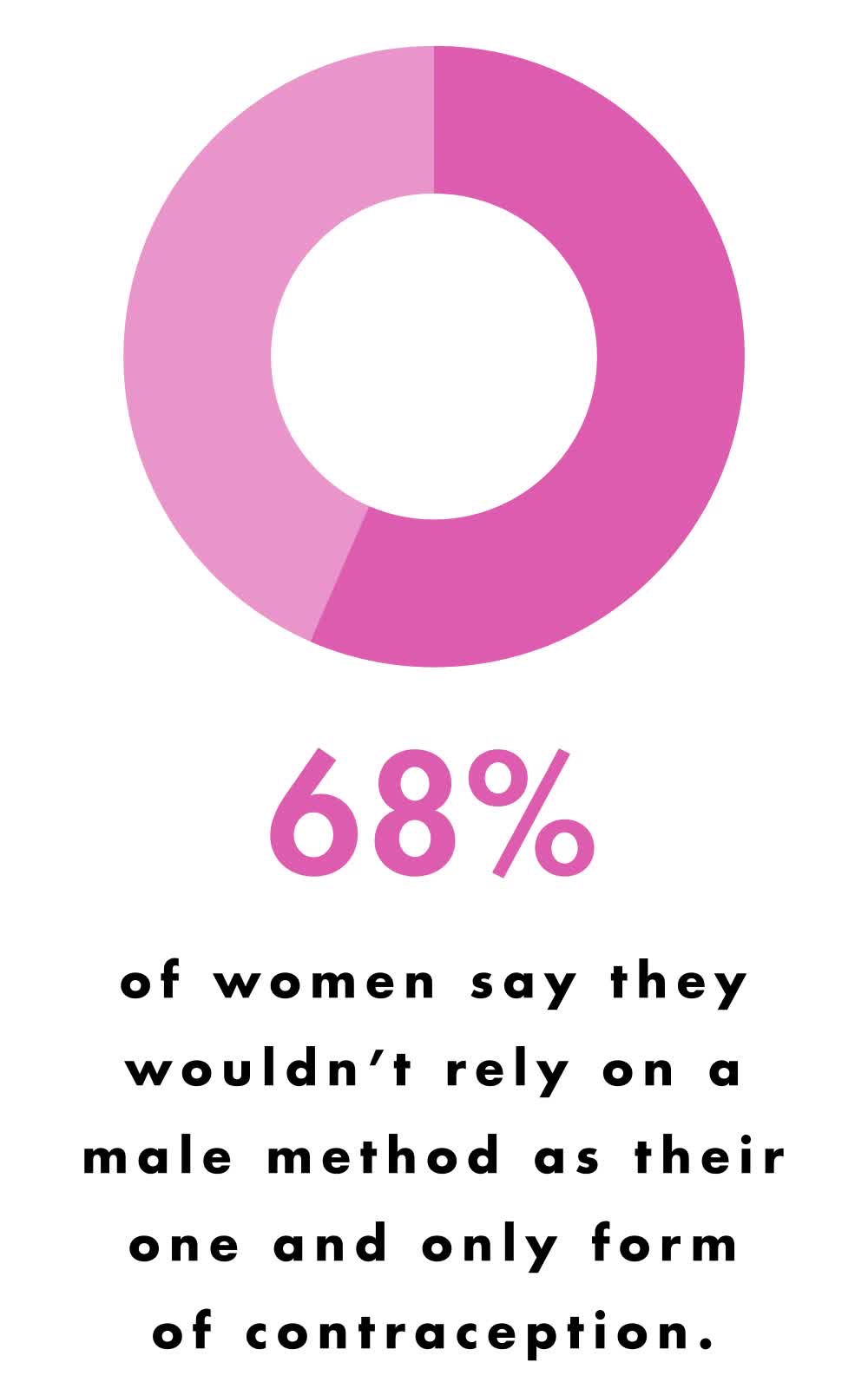

We also found something else, something major: Many of these hang-ups—the very reasons male birth control has stalled again and again—are lies. Researchers have discovered methods that work, and men want their own birth-control options. And according to an exclusive Cosmo survey, women overwhelmingly want men to have them too.

“But wanting male birth control is different than us being able to get it approved,” says John Amory, MD, a medical professor at the University of Washington School of Medicine at the forefront of the latest male BC trials. Here’s why it’s still out of reach.

It’s not that it’s not possible

As women know, all birth-control methods have to be three things: effective, reversible, and safe. And it’s taken scientists a very long while to achieve all these for men (for a play-by-play, scroll all the way down and peep the timeline).

After all, it’s no small feat to prevent the 800 million sperm in a single ejaculation from doing their thing, says Diana Blithe, PhD, program chief with the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s Contraceptive Development Program.

In 1974, Elsimar Coutinho, MD, thought he’d hit the trifecta with gossypol, an oral contraceptive for men that used a chemical from cotton plants to reduce sperm count. But it was kiboshed before it ever hit the market when studies found that it wasn’t so reversible after all. Since then, researchers have focused on hormonal methods, including weekly testosterone shots, that have been proven to be both effective and possible to undo. But products keep hitting the same snag: the third requirement, safety—or what women who’ve been taking birth control forever know as side effects.

Issues like weight gain, acne, and mood swings—the stuff we deal with daily—have, at one point or another, shut down an otherwise successful male contraceptive drug trial. In 1996, the new potential It Drug for men was shots of testosterone, but after testers complained of weight gain, decreased testicular volume, and the weekly shot schedule, it was killed. Ten years later, another clinical trial of testosterone and progesterone shots fell apart when men started dropping out after experiencing muscle pain, acne, depression, and changes in sex drive.

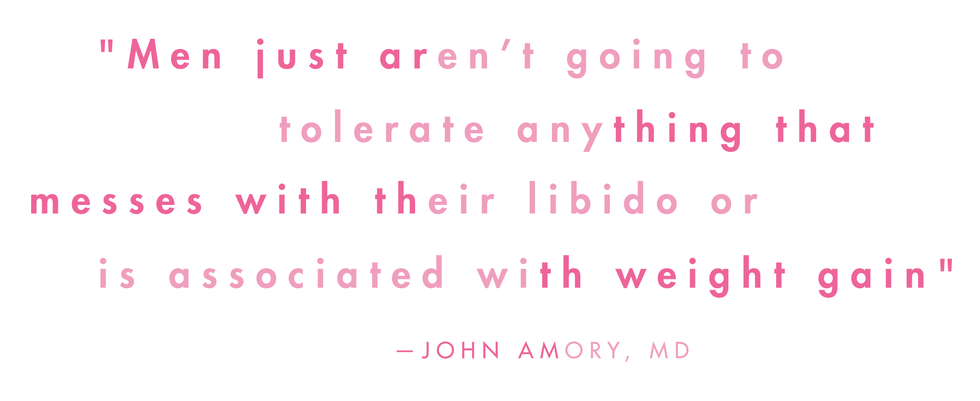

“Men just aren’t going to tolerate anything that messes with their libido or is associated with weight gain,” says Dr. Amory with a sigh. And major pharma companies with the funding to field drug trials are obviously not going to be motivated to put money or marketing behind a product that might not even interest their clientele. (Case in point: Dr. Amory says he doesn’t consider pharmaceutical funding an option for male birth control these days. His current research—a clinical trial of a hormonal gel that reduces sperm—is being bankrolled by a small pile of government funds allocated to all contraceptive research, including more options for women.) Plus, the thinking has gone, if some new male contraceptive option went haywire after a few years, men might sue for big bucks.

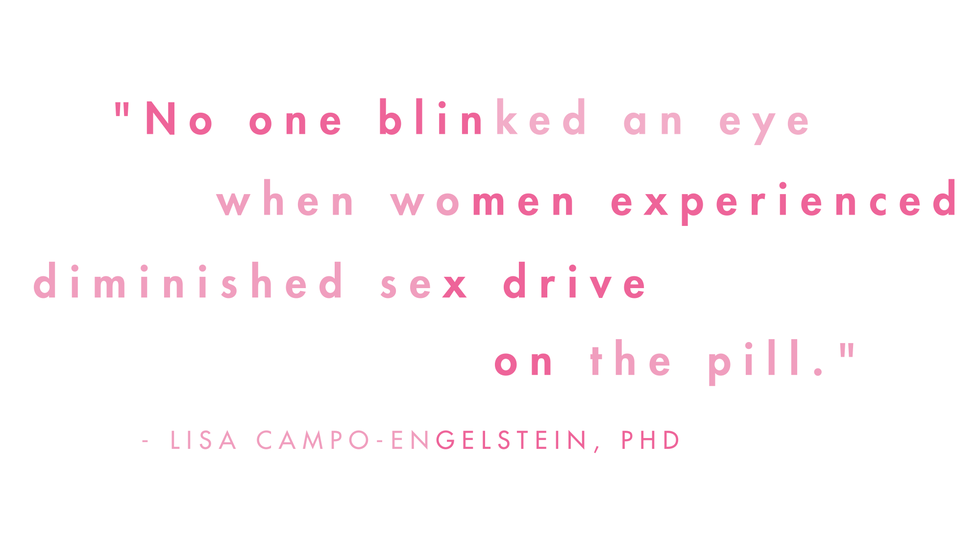

So yes, you are correct: This is pure sexism at play, confirms Lisa Campo-Engelstein, PhD, an associate professor of bioethics at Albany Medical College. “No one blinked an eye when women experienced diminished sex drive on the pill,” she says. “But when that’s happened for male contraceptives? People say, 'No way, that’s part of what it means to be a man.’”

That’s nice. But what about us?

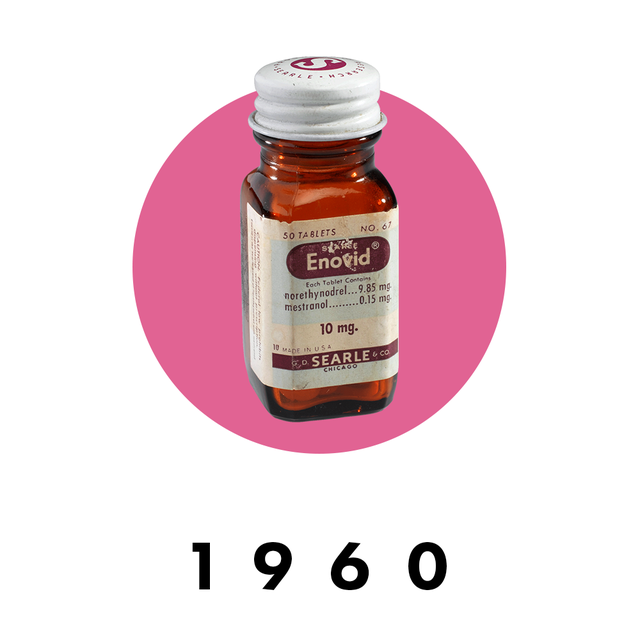

At the same time as all this testing and retesting and dead-ending has been going on, dozens of types of female birth control have been approved, like the now-ubiquitous birth-control pill. “Women had a huge demand for this product,” says journalist Jonathan Eig, author of The Birth of the Pill. But meeting that demand came with a double standard that’s allowed men to stay off the hook, he adds, sometimes even at serious risk to women.

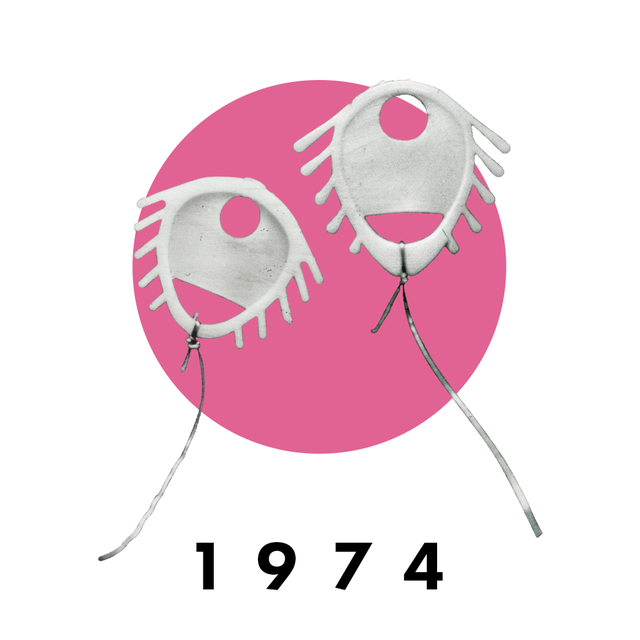

Take Enovid, approved in 1960, which contained literally 10,000 times the amount of estrogen in today’s low-dose pills. Women had been taking it for several years before anyone realized it had serious side effects like blood clots and stroke. In 1974, the Dalkon Shield, an early IUD with an alien-sounding name, had to be pulled from shelves because, after three years on the market, it was causing issues like severe pelvic inflammatory infections, pregnancy complications, and even death.

So, yeah, women have been through a lot—yet a few guys complaining of side effects we consider normal in a trial is enough to kill a potentially viable male BC option. Experts say this all stems from a stuck-in-the-’60s mentality, when women were willing to stomach just about anything to be able to have sex as freely as men did. “Back then, women had a lot of incentive to put up with side effects or at least see how bad the side effects were going to be,” explains Eig. (In fact, when Dr. Coutinho presented his male BC at a UN Population Conference, he was booed off the stage by an audience of mostly women. They had just been given control over their reproductive health a few years prior—and they weren’t about to give it up to men.)

“One of the unintended results was that men became passive and developed the attitude that they didn’t have to take any responsibility,” adds Eig. “So by the time we got around to actually contemplating birth control for men, they had checked out.”

Today’s guys aren’t actually checked out though

It’s not surprising that drugmakers might believe the juice isn’t worth the squeeze on male BC. But it is—or at least it could be: “Men today are much more interested than they used to be,” says Campo-Engelstein, “even though there’s still the perception that they’re not.”

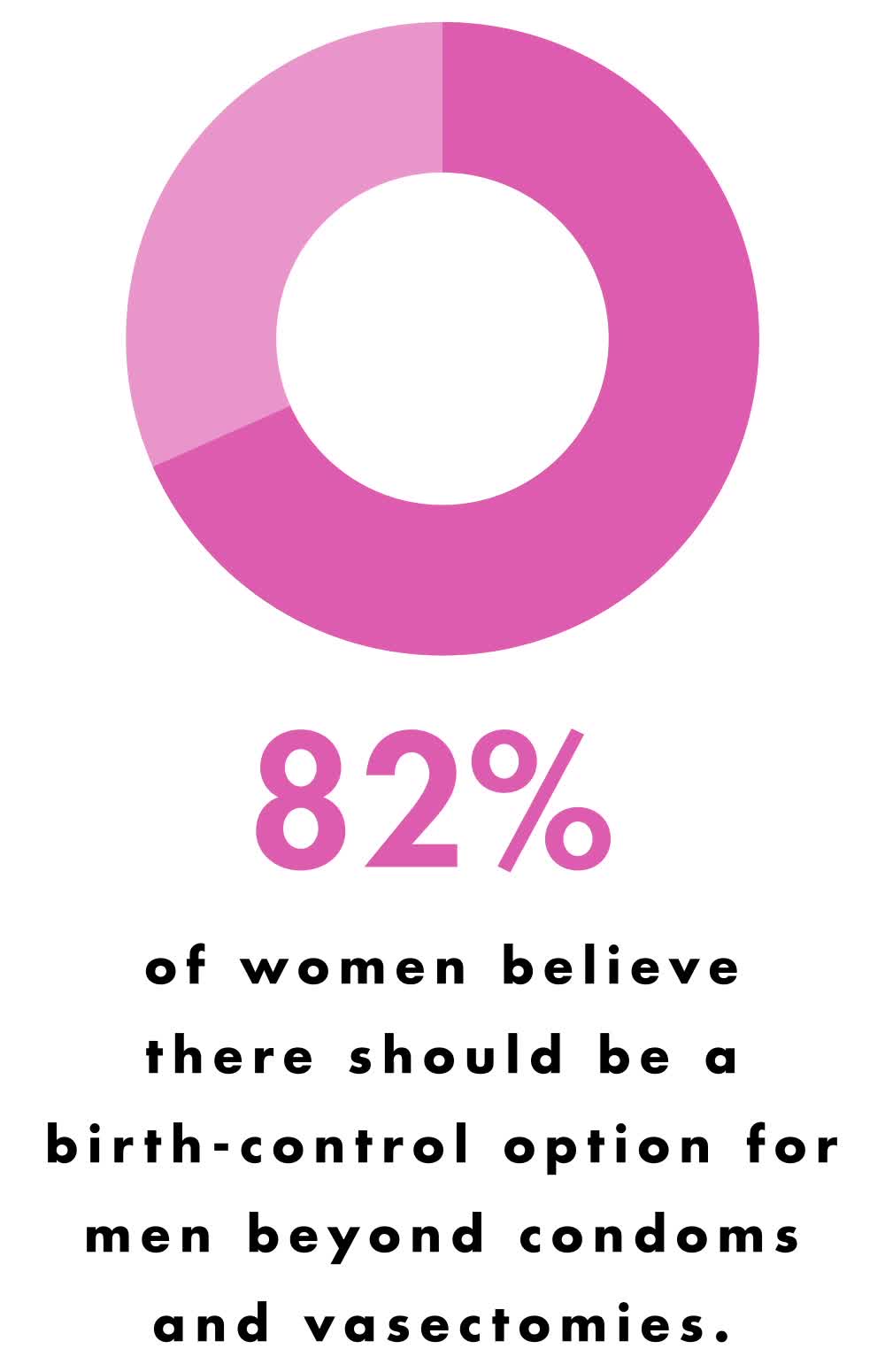

The honest, modern, up-to-date truth: Today’s guys really, really want their own contraception beyond condoms. A whopping 77 percent of men between the ages of 18 and 44 who have sex at least once a month are “very or somewhat” interested in taking birth control, according to a recent survey by the Male Contraceptive Initiative, an organization that helps fund and facilitate research on male contraceptives. When asked what kind of method they’d use, most men said they’d want either a pill they pop right before sex or one they take every day.

And get this: Only one-third of men who are on the fence about male birth control said they were concerned about possible side effects. In interviews with Cosmo, guys said they’d be happy to deal with reasonable side effects of taking birth control if it meant they’d have more of a say in contraception. “If you’re in any sort of relationship, you agree to share any burdens, and birth control is unequally distributed on women,” Jeff Fitzgerald, 27, told us.

Harris Bransch, 25, agrees. "Birth control shouldn’t be one person’s responsibility. There are two people who are trying not to get pregnant."

It’s about time, according to you: A staggering 98 percent of Cosmo readers believe there should be a birth-control option for men beyond condoms and vasectomies. And while most of the women we talked to wouldn’t necessarily trust a random hookup to accurately use or take it (totally fair for both sides, TBH), in the context of a relationship, nearly 100 percent of women told us they’d ask a partner to use long-term male BC if it existed—and that they hope it does soon.

Okay, so give it to us?!

Men want it. Women want it. So the science doesn’t need to be held back anymore by outdated, sexist beliefs. As a solve, Dr. Amory and others in his field are appealing to the FDA by trying to change the way the government thinks about reproductive responsibility and risk. They’re going to show them the same receipts we just laid out for you, in the hope that the major decision-makers wake up to the idea that men and women should carry equal (or at least more equitable) weight when it comes to BC—and that men need to finally take a more active role in preventing pregnancy.

And then there you’ll be, sometime, hopefully not too far from now, picking up your BF’s BC gel at the pharmacy or going with him to get his baby-blocking implant put in. Wait...what are we even saying? He can handle picking up his birth-control prescription himself. It’s been half a century. You deserve a break.

Photographed by Hannah Whitaker. Props styled by Elizabeth Press for Judy Casey. Grooming: Deepti Sadhwani. Inspired by a photo by Ethan Pines. Timeline (all but 1832): Getty Images.