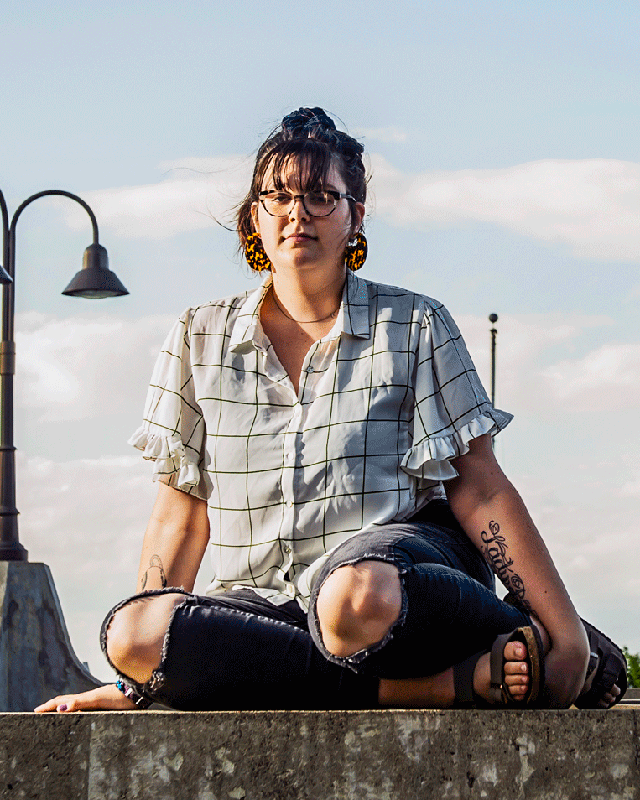

In August 2016, when she landed on the leafy, almost comically picture-perfect campus of Ithaca College in upstate New York, Makai probably seemed, to the other freshmen, like she was doing just fine. She fell in quickly with a core group of friends, and soon they were watching TV in the lounge, cruising to house parties, and venturing over the hill to frats at neighboring Cornell.

No one could see that Makai was completely spinning out.

She sometimes got so gripped by social anxiety that she could barely form sentences. Sitting with her new friends in class or eating in the dining hall, she could feel her heart racing so fast that it made her dizzy. Her new crew was so foreign, so East Coast, with their preppy clothes and still-married parents, whereas Makai, who was raised by her mom after her parents divorced, still wore the thrift-store sweaters that had fit in perfectly at her artsy California high school.

She’d never partied so much. She’d never felt so on display, like her sexual worth was being assessed by guys every time she walked into a room. She went along with it, but keeping up the cool-girl charade was exhausting.

After going out every night for weeks, Makai got so overwhelmed, so tired of it all, that she locked the door to her room and didn’t come out for days. Holed up in bed, she pretended to be sleeping to avoid her friends’ texts. She didn’t want anyone to see she was suffering. She didn’t want to be known as the girl with mental illness.

Makai had had anxiety and depression for years, diagnosed when she started seeing therapists at age 14. She was on prescription meds, but now she wondered if they were even working. She had always planned to seek help once she got to campus. She just didn’t know how quickly, or how urgently, she’d need it.

In late September, feeling desperate, she called psychological services.

A woman on the phone told her, “Someone will be in touch to book an appointment.” But for two weeks, no one called. When her phone finally did buzz, it was an intake person asking about her symptoms and medical history, who then said she’d have to wait three more weeks to see an actual therapist.

In October, a guy Makai liked, who seemed to like her back, hooked up with one of her friends. Needing to escape from everyone and everything, Makai retreated to a spot behind the dorm where she sometimes sat to think. Oh my god, she told herself. This is really getting bad.

She hadn’t cut herself in almost two years. But now, back in her dorm room, she reached into her desk drawer and pulled out a Swiss Army knife.

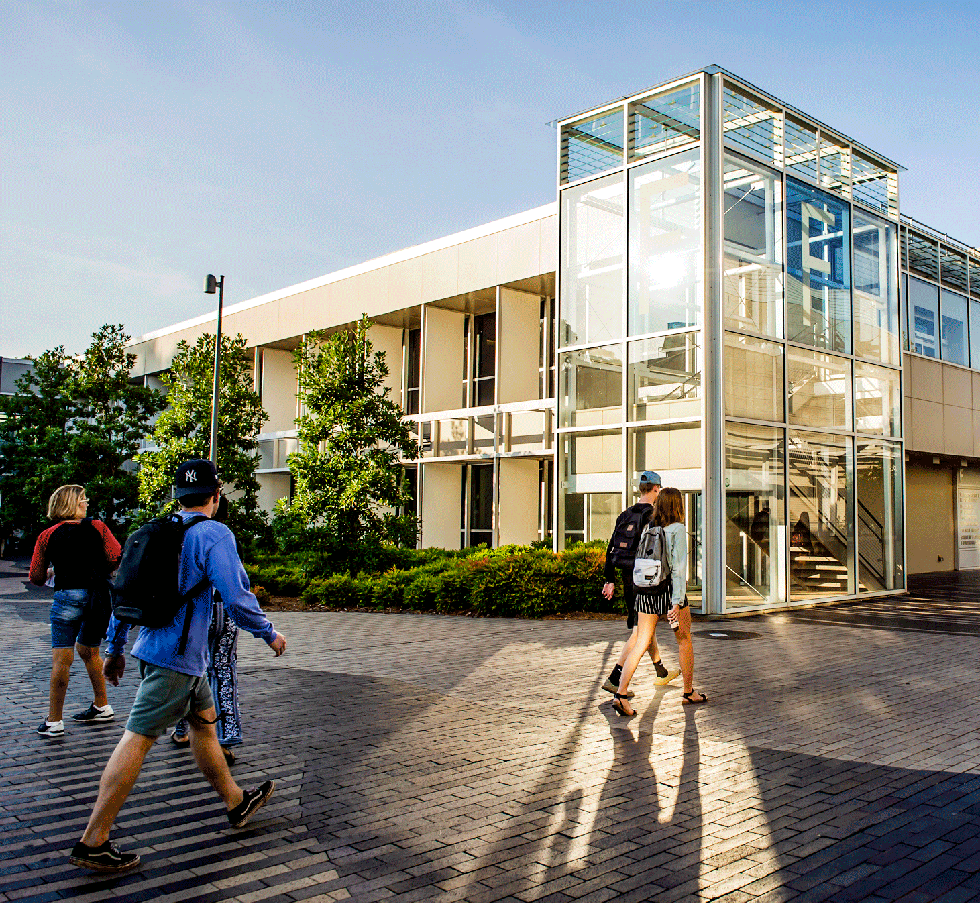

Between 2010 and 2016, the number of students seeking on-campus counseling shot up by 30 percent—more than five times the growth of overall college enrollment. The result: By 2018, 34 percent of school health centers reported wait times, per the Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors (AUCCCD). For students on those lists, the average wait time was 17 business days. But at some schools, it stretched to 34.7 days. That’s seven weeks, FYI, or half a semester.

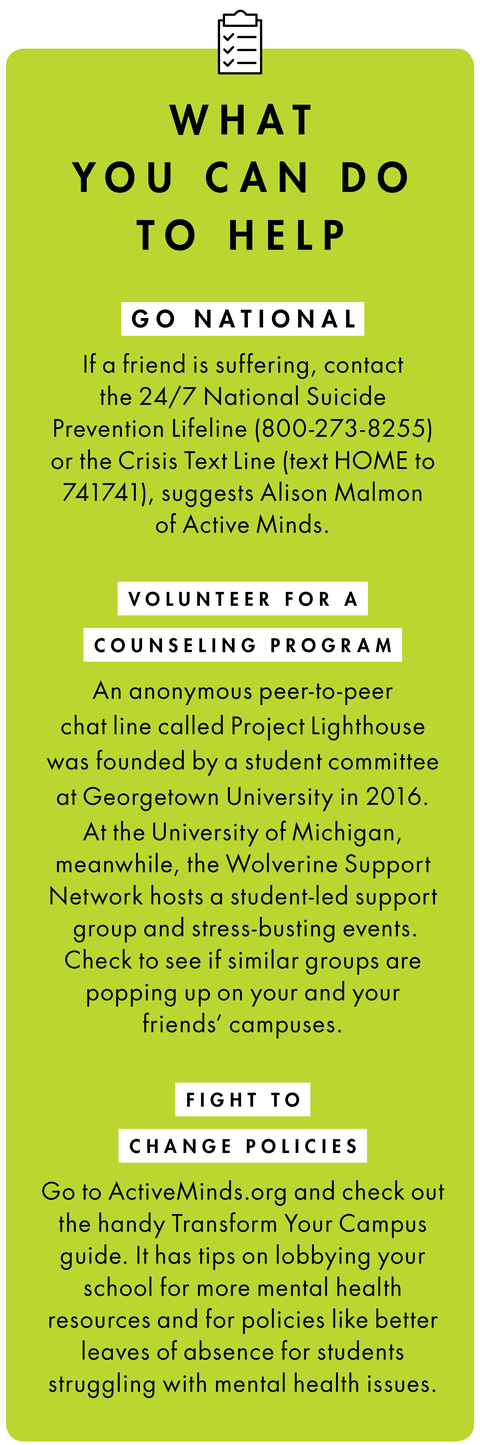

“We’re hearing it more and more,” says Alison Malmon, the founder and executive director of Active Minds, a network of student-run groups that promotes mental health awareness. “What used to be a problem of a two-week wait time has now become four to five weeks.”

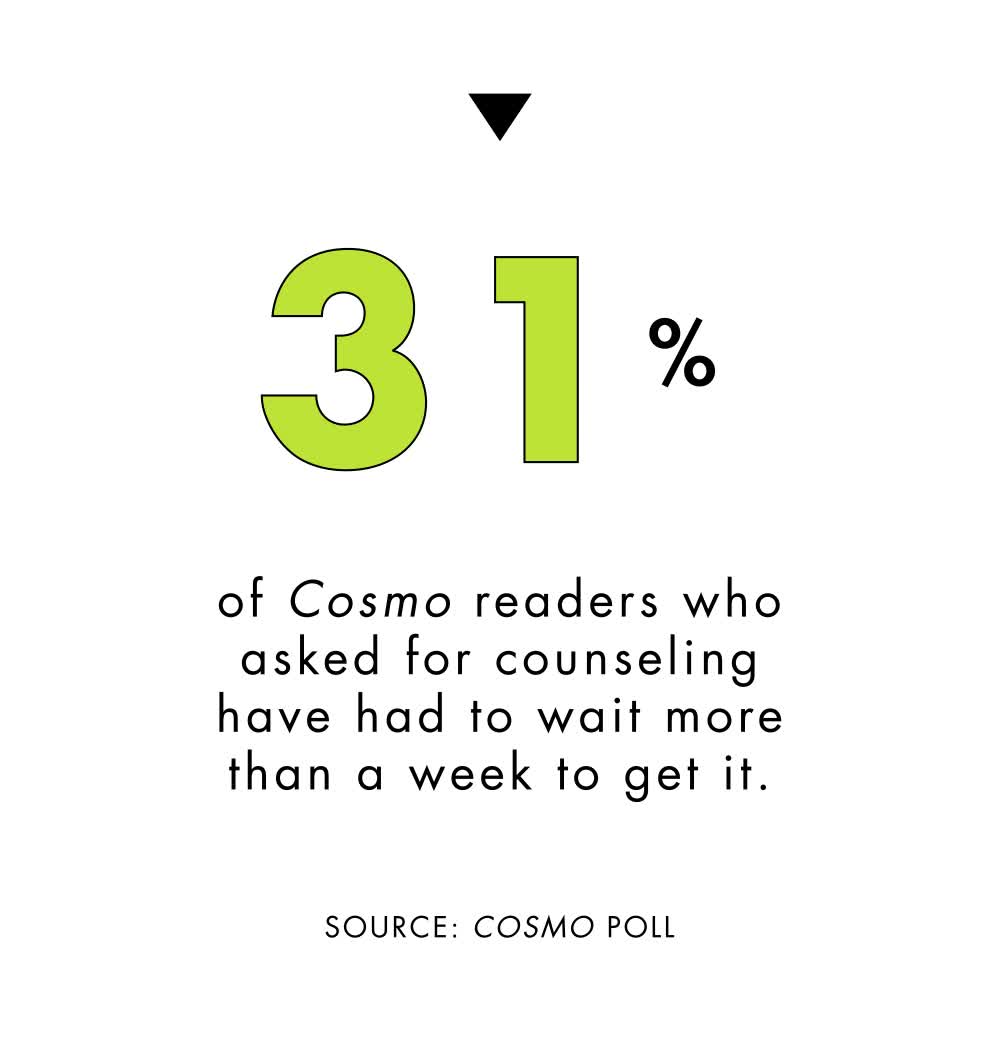

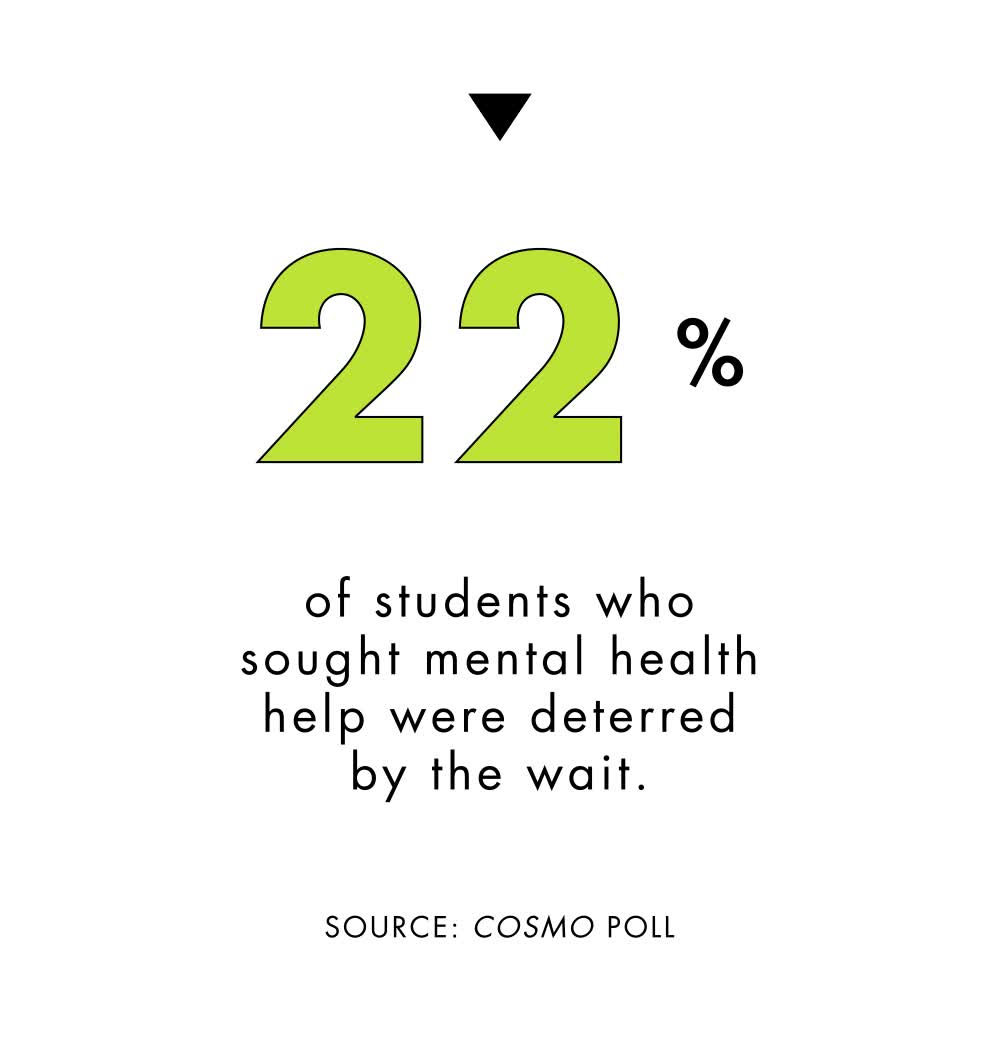

Cosmo’s own data confirms these stats. Among the college students we talked to who had asked for counseling, 61 percent said it took a week or more to see someone; 21 percent said more than two weeks.

“The longer people wait, the fewer of them show up,” says Joe Parks, MD, medical director at the National Council for Behavioral Health. In his own practice, he decreased no-shows from 30 percent to 5 percent when he started scheduling patients the same week they called. (In Cosmo’s survey, 44 percent of respondents said that a wait put them off the idea of getting help.) For students who are far from home, especially, “long wait times can increase feelings of hopelessness, heightened anxiety, and more sadness and depressive symptoms,” says NYC-based child and family psychologist Jennifer L. Hartstein, PsyD. “This could lead to acting out in risky ways.”

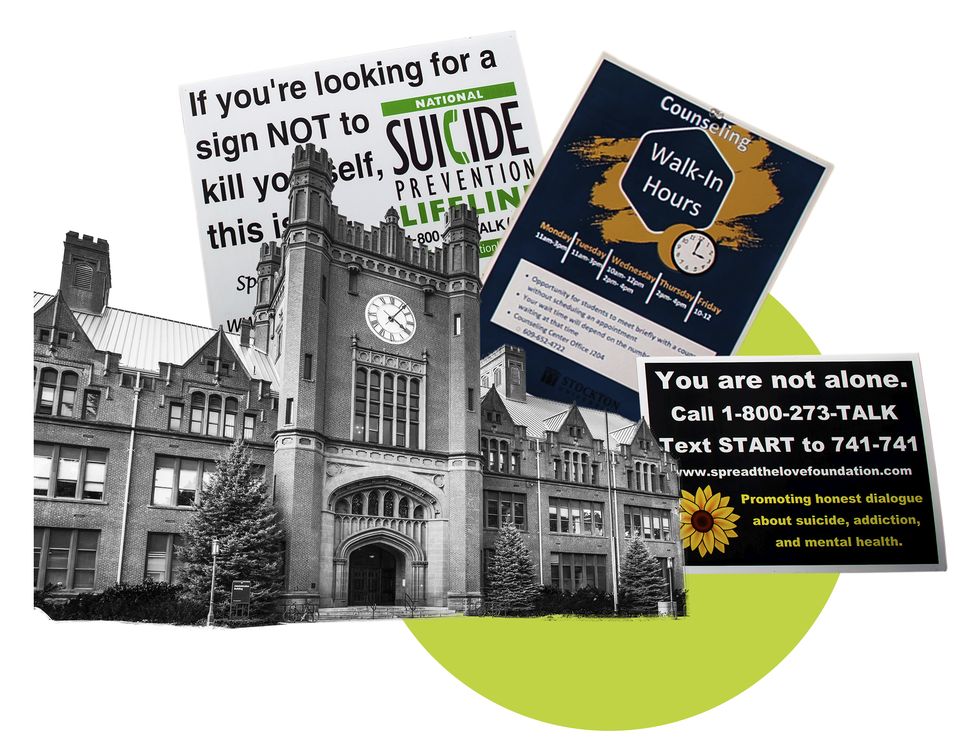

Last December, a student at Rowan University in New Jersey died by suicide in an off-campus parking garage. It’s impossible to know what, if anything, could have prevented this tragedy, but Rowan’s wait time for counseling services—reported to be months—was no secret. In the wake of his death, grad student Summer Dixon posted an online petition arguing that the school “NEEDS better mental health resources!” (Rowan says that only students whose cases have been identified as “non-urgent” face possible wait times.)

“I have personally struggled with my own mental demons,” Summer wrote. “When seeking out resources, ones that Rowan openly advertises, I found a giant wall. A wall preventing me from getting the help I need.” At Northwestern University in Illinois, after four deaths by suicide in 2018, student protesters took to the streets to call out their school’s mental health resources.

Malmon says our brains change rapidly until the age of 25, so the high school and college years are when mental health issues commonly surface. And today, a shocking proportion of college students report being deeply, worrisomely unhappy. In the spring semester of 2018, 53 percent reported having “felt things were hopeless” within the past year, according to the American College Health Association. Twelve percent said they had “seriously considered suicide.”

Part of this can be blamed on the specific (and outrageous) pressures of being young in 2019. But high counseling demand also has roots in something more positive: mental health being increasingly destigmatized. “In previous generations, people suffered silently,” says Barry Schrier, PhD, director of the counseling center at the University of Iowa and chair of the AUCCCD’s communications committee. Today, “more students have decided, ‘I want help.’”

But these students may not have the wherewithal, while they deal with self-harm or suicidal thoughts, to advocate for an earlier appointment date too. “Not everybody knows how to say, ‘I’m in a crisis,’” Malmon says. Being put off “can feel like a rejection.”

Soon, Makai was slicing angry red marks on her arm a few times a week, locked in a bathroom stall or alone in her room. She wasn’t trying to seriously injure herself. The physical pain was just a way to dial in, she says, to pull the focus from her emotional pain. Stanching the blood with a tissue, she was embarrassed that she’d have to wrap her wrist in an ACE bandage and make excuses to her new friends—and that she was right back here, in this place she’d worked so hard to move on from. She felt out of control. She felt, increasingly, like she was going to implode.

On many campuses, alternative resources like group therapy are available for students who can’t immediately see a provider. But what Makai really wanted was one-on-one sessions. Most students Cosmo spoke to said the same. When Angela, 21, a senior at the University of Texas at Austin (UT), suffered a devastating breakup sophomore year, she felt alienated from her friends (who were also her ex’s friends) and couldn’t stop sobbing in her favorite coffee shop. It took two weeks to see a therapist, who, as a fellow Asian American, understood her reluctance to open up about her feelings. The stigma around therapy, Angela says, is strong in her community. But after one session, the therapist referred her off campus for more treatment.

Angela didn’t have a car. She also didn’t feel comfortable with the group therapy sessions she was offered, which would require telling a group of strangers about her convoluted romantic situation. So she just tried to cope on her own. Until the next semester, when things got bad again and she landed back in the counseling center.

In two years, Angela says she saw four different on-campus therapists, for one session each, after waiting up to a month. (Marla Craig, PhD, senior associate director for clinical services at UT’s Counseling and Mental Health Center, says any student who seeks help can see a counselor immediately but that they might then be referred off campus for continuing sessions or to services like group therapy. The center then helps deal with insurance and transportation.)

Schools say they’re happy more students are asking for help but that they just lack the resources to provide ongoing individual therapy to everyone who wants it. “Face-to-face, weekly, individual counseling is a fairly high level of care,” says Schrier. At UT, some 14 percent of the school’s 51,000 students, or more than 7,000 people, seek mental health help each year, says Craig (in an AUCCCD report, the average for large universities was between 6 percent and 8 percent), but the school has fewer than 30 full-time counselors. A majority of counseling center directors across the country said they don’t have enough psychiatrists to treat the need on their campuses, per the AUCCCD.

Some campus counseling centers don’t have the money to hire more staff. Other schools arguably do but haven’t allocated the funds for it. (Some colleges, like the University of Iowa, now charge students a mental health fee on top of tuition—but even this hasn’t totally eliminated wait times.) Location can make a difference too. In rural areas, where there are few trained mental health professionals in the community, “that trickles onto campuses as well,” Schrier says.

Most schools do prioritize students who say they’re in imminent danger—but not all students can do this. Some downplay their symptoms, since they’re so common. “No one’s sleeping. No one’s eating,” says Leah Goodman, a visiting clinical instructor who designed and teaches a course on mental health and wellness at the University of Illinois at Chicago. “Students are like, ‘It’s fine,’ when more often than not, it’s not fine.”

Still, Schrier says it’s unrealistic to expect that everyone can get therapy on demand: “I don’t call my dentist’s office and hear the dentist say, ‘We’re not doing anything right now, if you want to come by.’” Craig, of UT, says students tend to resist group therapy at first but then ultimately end up liking it.

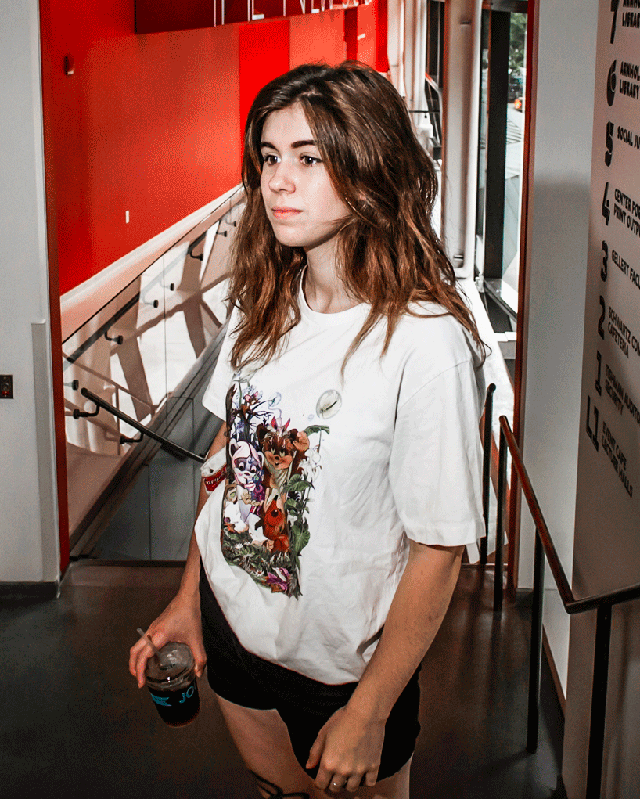

But for Emily, 23, a lack of access to regular one-on-one therapy was one reason she transferred out of Cooper Union in New York City to a community college in 2016. Anxious, depressed, and sleepless, she was initially able to see a therapist weekly. But after a semester off, she returned to find a new two-session limit, after which she was “outsourced,” she says, to an off-campus provider whose office was far away and had few convenient appointments. “It got to the point where I stopped going,” she says.

After that, “my mental health went so downhill.” She had been sexually assaulted the previous summer and felt alienated in her male-dominated engineering program. “My schoolwork was taking a hit. I wouldn’t go out with friends. I’d go to class, come home and lie in bed, and not be able to sleep. Eventually, I was like, I don’t want to do engineering anymore, I hate this, I can’t do it, no one believes in me, no one cares.” (Cooper Union says student wellness is “an important priority” and that its off-campus providers are all “within walking distance or a short subway ride” of its campus. The school says each student gets six free counseling sessions per year before insurance is billed.)

It was November 2016—five long, painful weeks after making that first call—when Makai finally sat in the basement of her school’s health center across from a counselor. Just getting there felt like a victory. When she told the woman she’d been locking herself in her room and cutting, the woman said, “I’m sorry you had to go through that. That’s really hard.” For weeks, Makai had been wondering if she was blowing things out of proportion, wondering why she couldn’t just deal. Now it all sunk in. You know what? she thought. It has been really hard.

For her, therapy wasn’t a magic bullet, and she’d still face a weeks-long wait to see a psychiatrist that the therapist referred her to. But it did make her feel hopeful—and put her on the path to adjusting.

Across the country, schools are finding creative ways to get more students to that first appointment. Arizona State University has 72,000 students and, remarkably, zero wait time, says Aaron Krasnow, PhD, associate vice president of ASU’s Health Services & Counseling Services. Anyone who calls is seen that day, “often the minute they walk in,” for as long as necessary—could be 15 minutes, could be an hour and a half. This appointment feels like a real session, he says, and not an intake call, which is all some students require.

“Some people just need help having a conversation with a professor or with their financial aid, or they just need to unload something that’s on their mind,” says Krasnow. When students like this end up languishing on waiting lists, it “creates a logjam for all.”

Krasnow believes wait times can be eliminated—and if they haven’t been, that’s evidence that stigma still persists around mental health. Which is why more and more students are demanding change. When word spread that the University of Maryland had a wait time of 30-plus days, the student group Scholars Promoting and Revitalizing Care launched the hashtag #30DaysTooLate, which landed the issue on the local news. At Stockton University in New Jersey, Julie, 21, met with the student senate and lobbied administrators to hire more counselors after having to wait for up to a month between appointments. (Stockton, like other schools, won’t comment on individual cases, but a spokesperson said, “Crisis-intervention services are available immediately as needed. The counseling center has daily walk-in hours for meetings with counselors and offers a web-based program called Therapy Assistance Online.”)

At Northeastern University in Boston, Kavita, 23, helped start the group Students Working for an Accessible Northeastern, which drafted a list of mental health demands, including more counselors. As a sophomore, Kavita had been nearly snowed under by sadness. “Depression is like an emptiness—a void,” she says. At one point, she wondered, What if I just took a few too many pills? But when she tried to book therapy, “it was always in three to four weeks,” she says. And it wasn’t just what the clinic was telling her, it was the way they were telling her. “I felt like my issue didn’t matter,” she says. (A spokesperson for Northeastern says, “We recognize that this is an area where we have room for improvement in order to provide the best care for our global community. This year, we are making significant investments to enhance our in-house staffing and resources as well as partnering with organizations to provide 24/7 care and appropriate referrals.”)

Goodman believes that better follow-up can ensure that wait-listed students at least know the school is trying to get them help. After seeing one of her students being turned away by the campus mental health clinic, she believes staff should receive training “so that every interaction for a student will be positive, particularly in a sensitive moment.”

Nance Roy, a professor of psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine and chief clinical officer of the Jed Foundation, which works to strengthen mental health among teens and young adults, agrees that every interaction is crucial. “We work with schools to create a culture of caring and compassion,” she says, “where there is no wrong door for a student to walk through to get support.”

It’s now been three years since Makai was a freshman at Ithaca. In that time, the school has hired two more counselors, added daily crisis hours, and installed an on-call counselor who’s available by phone 24/7 whenever the counseling center is closed. It has also streamlined the intake-call process that added two weeks to Makai’s wait.

Since most of these changes are new, it remains to be seen whether they’ll bring down wait times, says Rosanna Ferro, PhD, who was appointed vice president for student affairs and campus life in 2017. “We’re not always going to have it a hundred percent right,” she says. “But it’s critical for us to get as close to perfect as possible.”

Now a senior, Makai has joined her local chapter of Active Minds, helping other students who are struggling (and struggling to stand up for themselves). And she’s stayed friends with that same once-intimidating crew, btw—only now they are her support system, not a source of stress.

“I think if I’d had help early on, I would have known better ways to handle the situations I was in,” she says, “which is what I did eventually learn from the counselor. But in the in-between time, I was kind of just left to fend for myself.”

Additional reporting by Natasha Jokic