Lyvonne Picou was a sophomore at Seton Hall University when a guy she liked gave her a copy of a book called I Kissed Dating Goodbye. The paperback had worn, dog-eared pages. On its cover, a young man tipped his fedora like Cary Grant…or like a finance guy dressed way too on-the-nose for a speakeasy bar he read about on Yelp. Nevermind the book’s title (Lyvonne and the guy never did get together)—she devoured IKDG, as it became known to its devotees, between classes and in random spots around campus. She found it “romantic—like a fairy tale.”

It’s a strange choice of words to describe a manifesto on extreme sexual abstinence. Harris promoted saving yourself for marriage, which Lyvonne—then a self-described born-again virgin who had fallen in with an evangelical crowd—was already planning to do. But as the title suggests, Harris went even further than that, making the case for giving up dating entirely—no hanging out with guys one-on-one, no kissing, even no holding hands.

Instead, people who wanted to get married should have a “courtship” approved by the woman’s parents. In IKDG and subsequent books, Harris said this would protect against heartbreak and sexual sin (plus store up more passion for marriage).

“I started romanticizing the idea of not being physical,” Lyvonne says. “My relationship would be ‘pure’ and perfect. I totally bought into it.”

She and some friends from her gospel choir set about following Harris’s dictates, trying to “keep my legs closed,” she says, so that “God would send me a chocolate man who was 6 foot 3 with a killer smile.” It wasn’t always easy—in the eight years that followed, she had slipups, each ending with a burning rush of shame.

Once, things got out of hand with a male friend, who kissed her and licked her nipples. She burst into tears. That she was a survivor of childhood sexual abuse only intensified her regret. “I felt ashamed of my body and trauma,” she says. “I didn’t know how to reconcile it with my faith.”

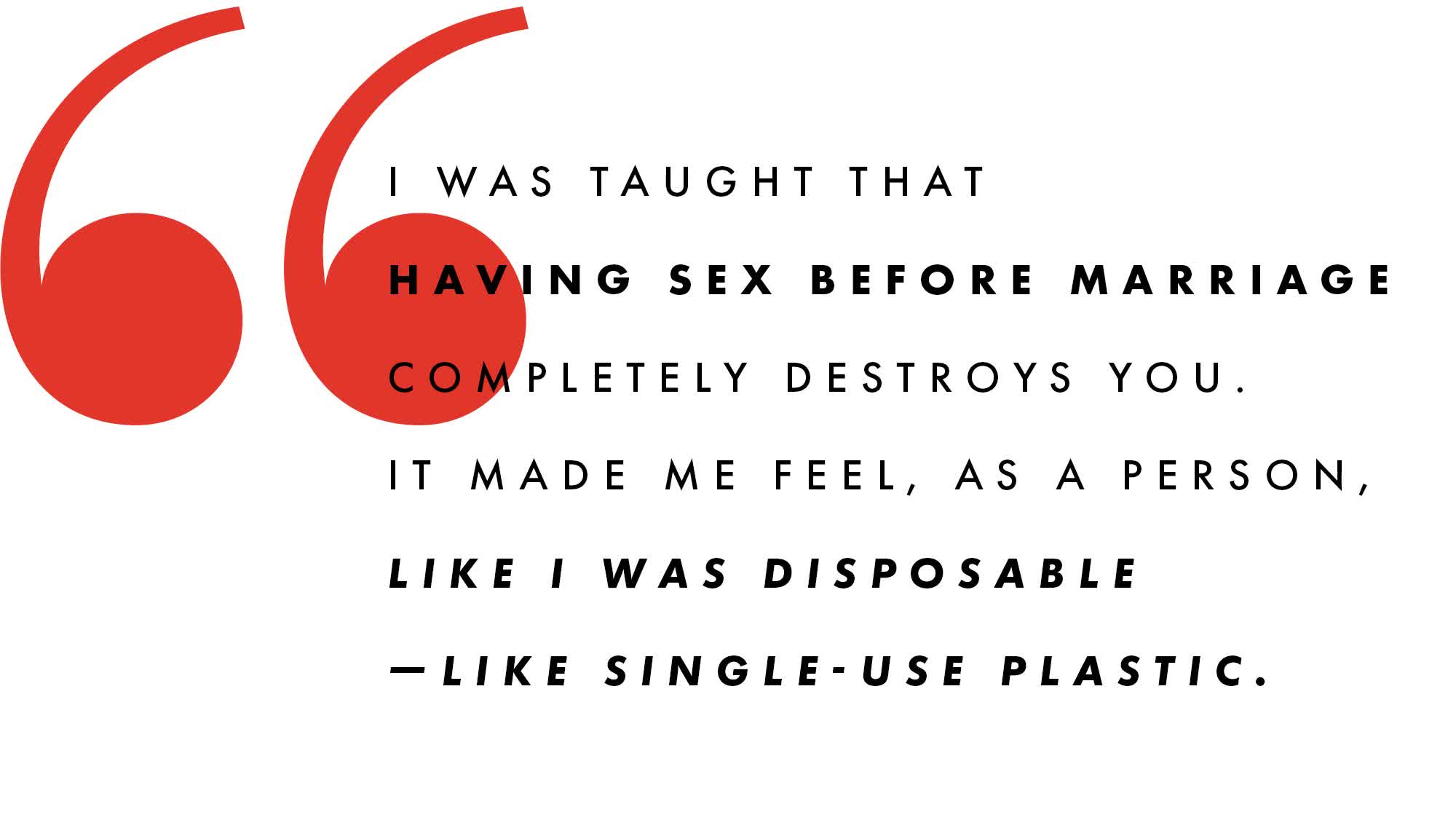

Lyvonne was far from alone: An extreme focus on sexual “purity” has left a generation of women riddled with shame, anxiety, and PTSD-type symptoms, writes researcher and former evangelical Linda Kay Klein in her new book, Pure. “We went to war with ourselves, our own bodies, our own sexual natures,” she says, “all under the strict commandment of the church.”

Using the hashtag #IKDGStories, which calls attention to the aftermath of Harris’s work, one woman wrote that her virginity had been so central to her self-worth that even after years of therapy, she experienced painful vaginismus (a severe tightening of the vagina often linked to anxiety around sex) when she tried to have intercourse.

Samantha Field, now 31, describes staying with a sexually abusive partner for years, believing that because they’d had sex, she was “disgusting garbage” that no one else would want. “I have to constantly fight against the lie that because I wasn’t pure enough, that because I had ‘dressed provocatively’ and allowed myself to be alone with him, that I invited it,” she wrote on her blog.

Lyvonne says she struggled with feeling “damaged, broken, dirty, and evil” for years. “We were supposed to kiss dating good-bye, but I kissed sexuality good-bye.”

Then last October, Harris, who had by then become an influential megachurch pastor, pulled a sudden 180 and disavowed much of his work, even going as far as to ask his publishers to stop printing IKDG and two books that followed it.

For the women who’d molded their lives to conform to his demands, moving on wasn’t so easy.

Joshua Harris isn’t solely responsible for the rise of purity culture, but he was perhaps its most persuasive prophet, especially among young women. The movement began in the 1980s and early ’90s when evangelical Christians started lobbying the government to fund abstinence-only education in schools as the AIDS crisis raged. An organization called True Love Waits, founded by the Southern Baptist Convention, popularized pledge cards with which young people could swear off sex “until the day I enter a biblical marriage.” The pledges spread from Baptist gatherings to Catholic churches to Christian rock concerts. In today’s lingo, they went viral.

And they kept spreading: In 1994, True Love Waits hosted a rally on the National Mall displaying more than 210,000 cards from teenagers across the country pledging to remain “pure.” Activists scored a meeting with President Bill Clinton. Four years later, Congress allocated $50 million annually for abstinence-only sexual education.

More than any other Christian religious dictate—like, say, feeding the poor—not having sex (or at least saying you were not having sex) became “the way for evangelical young people to live out their faith,” writes Klein. And they wanted the merch to prove it: purity rings, pins, and bracelets engraved with Bible verses—not to mention thong underwear emblazoned with “One life, one love”—popped up in online stores or in some cases at mainstream retailers like Walmart. Unlike Catholicism, which has clear doctrine and leadership, evangelical subculture lacks a traditional hierarchy. Early on, its ideas were spread by charismatic pastors and, later, televangelists and sprawling megachurches. Then came a thriving market of Christian pop culture: books, movies, music, and a circuit of hired speakers.

When Harris—the handsome son of a prominent homeschooling advocate who’d been publishing his own Christian teen magazine—burst onto the scene in 1997, it was primed for him. In IKDG, he told the story of his own conversion in personal terms. Formerly “girl crazy,” he felt called to live a more virtuous life, threw out a Penthouse magazine he had stolen (and returned to the store to pay for it), broke up with his girlfriend—they’d been “violating each other’s purity”—and wrote his blockbuster book in less than a year. That he was 21 when the book was published and not an ordained preacher was no problem. “Evangelicalism is built to give authority to men in particular,” says Dianna Anderson, whose youth group in South Dakota followed Harris’s no-dating model. “Even a 19-year-old man can become an authority on a subject because he says this is what God wanted.”

In its first year, I Kissed Dating Goodbye sold more than 118,000 copies, a feat for a small Christian relationship guidebook. (Today, that number has risen to 1.2 million.) Harris instantly made purity “cool” to young people. “If you are part of that homeschool culture or that larger evangelical culture and here’s this young, good-looking guy giving you instructions on how to be the kind of woman he would want to marry, you’re going to eat that up,” says Sara Moslener, a lecturer in the department of philosophy and religion at Central Michigan University.

Seemingly overnight, Harris had groupies. Samantha had been given a purity ring by her parents at age 16 (“Girls in our area would wear their rings until their wedding day and then gift them to their husbands in a nice box,” she says). After IKDG was published, fedoras became “de rigueur on campus” at her alma mater, Pensacola Christian College. “I didn’t have a crush on him specifically, but guys who sounded and acted like him became more attractive,” says Samantha. Harris even appeared on Bill Maher to discuss dating and relationships with Ben Affleck, who sagely asked how you’d ever find The One if you couldn’t date.

Emily Joy, now 27, grew up with Harris’s books—after IKDG, he would publish five more—and calls them “foundational to my understanding of what a healthy relationship should be.” And yet, as a teenager, his writing made her “hypervigilant of everything my body was doing at all times,” she says. She feared full-frontal hugs because if a boy pressed against her breasts, she might inadvertently cause him to have lustful thoughts, which, according to Harris, could set him on the path to damnation. Never mind that Emily was queer (she didn’t know it at the time). For years, “it felt like every muscle in my body was clenched,” she says, as she tried to avoid turning men on.

Samantha was also feeling the pressure. “I had such fear over my own sexuality,” she says. “The book taught me that it must be tightly restrained, almost viciously controlled, or you might die. Harris used that threat.” (In IKDG, he wrote of spiritual death in stark terms: “No matter how good impurity’s victims may be or how holy they’ve been in the past, if they set foot in her house, they speed toward death on an expressway with no exits.”)

After finally escaping her abusive ex, Samantha tried to have sex within the confines of a healthy relationship at age 25. “The first time I tried to give my now-husband a blow job, it was a massive trigger,” she says. “I was in tears, shaking, nauseated. I had to heal from a lot of trauma.”

On a Friday in November, I called Harris, who answered from a coffee shop in Canada, where he moved after leaving the ministry in 2015. “I deeply, deeply regret any part that my writing contributed to women being led to a really unhealthy view of their body, their sexuality,” he told me. His about-face began in 2012, when a sexual-abuse scandal rocked the megachurch where he was a pastor. The abuse happened before Harris’s time, but he was accused, with other church leaders, of not reporting allegations to police sooner (Harris left the church shortly thereafter). During this reckoning, he also heard from congregants about how the church and his books had harmed them. So last year, he finally posted a blockbuster statement to his website: “To those who read my book and were misdirected or unhelpfully influenced by it, I am sincerely sorry.…I regret any way that my ideas restricted you, hurt you, or gave you a less-than-biblical view of yourself, your sexuality, your relationships, and God.”

Now, he goes further. “When I look at the way courtship played out for the majority of the people and the environment it created, I do think it is a failed enterprise,” he says.

In November, Harris released a documentary titled 'I Survived I Kissed Dating Goodbye,' which features women and men talking about how the book affected them. But by then, not everyone was buying what he was selling (Harris says he will not profit from the film). The secular media was receptive, painting him as contrite and searching. But many ex-evangelicals remained skeptical.

Samantha and Emily helped start the #IKDGStories hashtag in part to ensure that Harris would not control the women’s narratives. Using the hashtag, women shared stories of waiting indefinitely for a husband to materialize, spending years lonely and riddled with guilt if they masturbated, or blaming themselves for their sexual abuse. Harris asked for permission to use some of the stories on his website and his documentary, but Samantha and Emily, at least, were suspicious of Harris’s true motivations.

To some of these women, Harris’s so-called apology tour still feels incomplete and convenient, like a desperate plea for relevance or a rebranding rather than a serious reevaluation. “I don’t remember where I was when he issued his apology, but I was pissed,” says Emily. “It’s very clear to me from the documentary that he is sorry for the wrapping paper of his beliefs but not the actual beliefs themselves.” To her, Harris hasn’t gone far enough to address the LGBTQ community. “Instead of making a documentary, maybe he should just come back to us once he’s unlearned it all,” she says. “Come back to us when you’re sex-positive.”

One woman on Twitter cut him more slack: “I feel bad for Josh Harris these days, to be honest....He has to live with a lot of people’s pain.…But he was 21. Everyone’s dumb at 21. No publisher should have given him the time of day. No Christian leaders or parents should have given his message that kind of power.”

Harris, for his part, tells me, “I basically started to see that real harm can come even though there are good intentions....I wish I had seen these problems sooner.”

If for some reason you’d like to snag a copy of I Kissed Dating Goodbye, you can still buy one on Amazon for $9. (It’s officially out of print, but others of Harris’s books remain in production.) Still, purity culture, while past its heyday, lives on, in daddy-daughter purity ceremonies and organizations like Silver Ring Thing, which preaches in high schools, churches, and other venues using “high-energy music, videos, dramas, special effects, and comedy.”

And although there may not be a new Harris on the holiness circuit, purity has other big advocates. Since President Trump took office, federal funding for abstinence-only education has surged for the first time since 2008. Meaning the sexist ideology that so many women say made them feel self-hatred and shame about their bodies will continue to be served up right after science class.

Some women are fighting back from within. Samantha is currently attending seminary and hopes to write about gender and politics in Christianity. Lyvonne eventually started therapy and became a pastor herself, focused on helping women—in particular black women—heal from sexual trauma and warped views of sex. There are so many out there, she says, left reeling by men like Harris. (He’s now running a marketing business in Vancouver.) Lyvonne wants these women to demand more from their churches. “You can’t do that if you’re sitting in the back pew,” she says, “cowed by anxiety, silenced by shame.”

This story appears in the March 2019 issue of Cosmopolitan on newsstands February 12. Click here to subscribe.

Sarah Stankorb is a writer whose work has appeared in The Washington Post, New York Times, The Atlantic, Vogue, Marie Claire, Longreads, Glamour, and Catapult, among others.